As the earliest existing film adaptation of Journey to the West, Cave of the Silken Web (1927), celebrates the 97th anniversary of its premiere in China, the 95th anniversary of its premiere in Norway, and the 10th anniversary of the return of the only copy of the film to the motherland in 2024. On June 6, the Jiangnan Branch of the China Film Archive officially opened in Gusu District, Suzhou. That night, a special screening of the soundtrack version of this silent film with deep roots in Suzhou was held.

"Pansi Cave" was produced by Shanghai Film Company, and some scenes were filmed at the Sword Pond at Tiger Hill in Suzhou. The lead actor Yin Mingzhu was also from Suzhou. According to historical records, the film "caused a sensation in Shanghai before it was screened", "(when it was screened) the streets were deserted, all cinemas were sold out, and people from Southeast Asia also rushed to buy copies." The box office on the first day of screening at Shanghai Central Theater alone was "more than 2,000 gold", "setting a new record for Chinese films screened in Shanghai".

Unfortunately, with the passage of history, almost all of China's early fantasy films from the 1920s have disappeared, and the original copy of "Pansy Cave" is hard to find in China.

Photos of the exhibition "Pansy Cave: Journey to the West and Return to the East" at the Jiangnan Branch of the China Film Archive

On April 15, 2014, the only copy of "Pansy Cave" that had been lost overseas for many years returned to China from the National Library of Norway and was re-screened at the China Film Archive, allowing domestic audiences to travel through nearly a century of time and space barriers and re-watch a precious piece of "footprints in the mud" that showcases the style of early Chinese films.

As one of the first audiences of "Pansy Cave" after it "returned to China", Professor Ishikawa of Shanghai Theatre Academy recalled that he was very excited and moved after watching the movie at the China Film Archive, "Everyone said at the time that the history of Chinese film in the 1920s might have to be rewritten." "In fact, it is not just this one film. With the re-excavation of a group of long-lost old films from the 1920s and 1930s represented by "Pansy Cave", it is necessary for us to re-examine and re-evaluate our own early film culture traditions." Recently, Professor Ishikawa accepted an exclusive interview with a reporter from The Paper.

【Oral】

The discovery of a unique copy has "overturned our understanding of early 20th century Chinese film history"

Now the Norwegian version of "Pansy Cave" is just a fragment, missing the opening subtitles of about ten minutes and the opening part of the plot. But even so, its documentary value is great, and the most important significance is that it almost subverts our existing understanding of Chinese films in the 1920s. Previously, the film scholars of our teacher's generation, Cheng Jihua, Li Shaobai, and Xing Zuwen, did not give a very high evaluation of "Pansy Cave" and its contemporary commercial genre films in their book "History of the Development of Chinese Film" published in the early 1960s. Because in their time, people's perspective and position on film cognition were different from today. They would not first look at the social and cultural attributes of films from the perspective of film type, commerciality or entertainment.

In the mid-to-late 1920s, when Pansi Cave was released, costume films, martial arts films, and mythology formed the three major types of domestic films, collectively referred to as "supernatural martial arts films", which was somewhat derogatory and easily associated with "supernatural powers". The martial arts films were represented by Burning the Red Lotus Temple (directed by Zhang Shichuan, released in 1928); the costume films were represented by Romance of the West Chamber (directed by Hou Yao and Li Minwei, released in 1927) and The Legend of the Righteous Demon White Snake (directed by Shao Zuiweng, released in 1926); the mythology films were represented by early adaptations of Journey to the West, represented by Pansi Cave (released in 1927) directed by Dan Duyu.

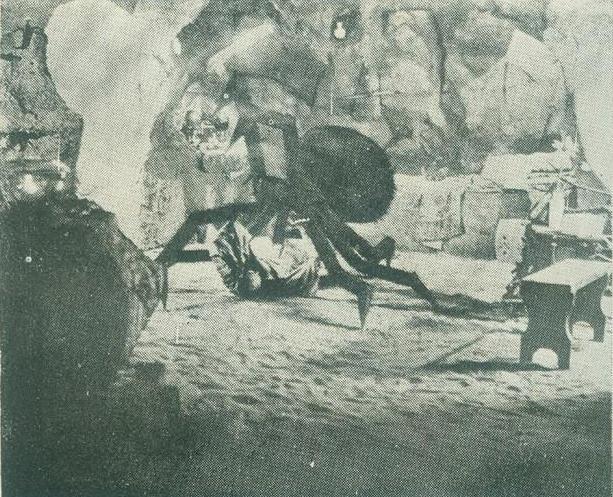

Stills from the movie "Pansi Cave". The spider spirit appears

When we look at these films today, we naturally have different criteria for judging them. At that time, the domestic film industry had already developed relatively fully and completely, and the film production capacity, total consumption, and technical equipment had reached a considerable scale and accumulation. This required more films to ensure the supply of the market, and it was obviously impossible to meet this demand by simply importing British and American films. So Chinese filmmakers began to turn to our traditional culture and traditional literature and art, constantly discovering and digging out new themes and new inspirations from martial arts novels, folk tales, traditional operas, and opera scripts.

As a film, "Pansi Cave" is actually a "visual modernization" of Chinese classical mythology. Before, people could only access the novel text, illustrations, or traditional art forms such as stage opera, shadow play, and New Year paintings. But after being made into a movie, it became a modern visual text with modern media as the carrier. Although "Pansi Cave" is not the earliest film adaptation of "Journey to the West", it is the only film we can still see today. Its huge cultural relic and documentary value is reflected in its "unique" attribute.

Stills from the movie "Pansi Cave". Fairy gets married, feast, singing and dancing

How a Chinese classical mythology is transformed into a modern cultural entertainment form through film is a very interesting topic in itself. For example, the wedding of the spider spirit in the film is very secular, which is equivalent to "demystifying" the classical mythology and eliminating its sense of distance from our secular life. No one has ever seen a monster getting married, but in the film we see that the monsters also have to worship heaven and earth, give gifts, sing and dance, and have a feast, which is almost the same as a mortal wedding. In this way, the mysterious, abstract, and distant ancient mythology has been transformed into a secular life scene that is no different from you and me.

Mysterious myths have thus become easy to understand, convenient for the public to read and consume, and popular with them. This technique has actually been used to this day. For example, Taiyi Zhenren in the cartoon "Nezha: The Devil Child Comes to the World" speaks "Trump", has a big belly, is greasy and cunning, and can use a hand mask to unlock the alchemy furnace... These are basically mythological imaginations that only young people in the Internet age have, and they also cater to the cultural consumption habits of the current audience. And the little demon Huo Nu played by Gu Yunjie in "Pansi Cave" is no different from the chef who cuts ducks in the kitchen while preparing meals; there are also two little spider spirits playing a rope-turning game, which is also innocent and romantic like a little girl in the alley. Through this technique, the myth of "Journey to the West" has completed a gorgeous transformation from classical to modern.

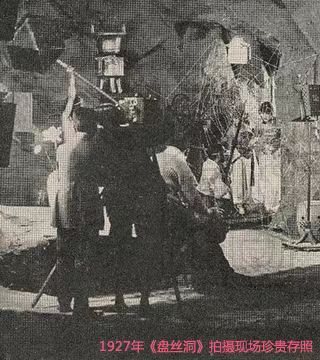

Photos from the film set of "Pansy Cave"

From the perspective of film creation itself, whether it is "ancient costume", "martial arts" or "mythology", they all represent the exploration of local genres of Chinese films. They all grew out of the soil of Chinese culture, which will not exist and cannot exist abroad. When movies are combined with traditional Chinese culture, a series of unique and rich local cultural languages and visual expression mechanisms are formed, which completely completes the localization transformation of the imported film - what we call "Chinese movies" today is that in the 1920s, through the hard exploration of that generation of filmmakers, it has become a new cultural reality. Traditional film history regards such films as "vulgar", "inciting obscenity and theft", and have no cultural value. From today's perspective, this evaluation is obviously unfair.

The copy of "Pansi Cave" was found in Norway, Northern Europe, which once again proves that Chinese films at that time had already joined the international cultural trade cycle. Some passages in the film were deleted, and even the Chinese subtitles were printed upside down, which shows how unfamiliar and cautious they were with Chinese culture at that time. But this is the true face of history. It was in this unfamiliarity, caution and disorder that Chinese films squeezed into the ranks of global cultural trade and exchange and became a member of the global cultural family.

In fact, mythological stories like "Pansi Cave" are not unique in early world cinema. For example, in Japanese and Korean films in East Asia at that time, there were also monster images such as fox fairies and beautiful snakes; European films had vampires - "bat spirits" that transformed from bats into human forms. These can be regarded as cultural references for "spider spirits" around the world. This shows that traditional cultural images such as "spider spirits" do not exist in isolation, but have similar echoes all over the world. This reminds us that we should use a more open global perspective to look back at our own existing cultural context.

Another point is that Pansi Cave still retains some of the unique film language of the silent film era that has disappeared today. For example, there are three different colors of film bases: one is gray, one is red, and one is blue. These colors are not just caused by technical reasons, but have specific symbols and meanings. For example, in the scene where Sun Wukong released the Samadhi True Fire to burn the demon cave, the film base is reddish, symbolizing fire. This is achieved by adjusting the mixing ratio of the reagents through darkroom technology during the film printing process. Correspondingly, the blue film base means that this is a night scene. Because at that time, the photosensitivity of most films was low, and it was impossible to shoot at night. The night can only be symbolically expressed with a blue visual effect. Today, these technical means have become a thing of the past, but with the re-screening of Pansi Cave, they have returned to people's vision like unearthed cultural relics.

"Blending painting into film", controversy and flaws cannot hide the charm of film art

On the first day of the Lunar New Year in 1927, The Cave of the Silken Web was released and achieved great success at the box office. However, it was also accompanied by some controversy, the most important of which was that in one scene, the spider spirit only wore a bellyband on the upper body, which was "exposed" and "indecent". From this criticism and controversy, we can see a certain self-contradictory "symptom of the times" in Chinese society and culture in the 1920s.

The film's director, Dan Duyu, was once a famous "calendar poster" painter in Shanghai. He was best at painting "100 beauties" on calendar posters. Even after changing his career to become a film actress, he was still an active figure in the Shanghai art world. His ideas were open and relatively "Westernized". He was fond of women as the subject of his paintings, and was particularly good at painting various female bodies using Western painting techniques. After switching to film, this style continued. Rather than saying that the "naked belly and bare back" of the spider spirit in his lens was immoral, it was more like representing an open, avant-garde, and modern cultural concept or aesthetic taste.

Actor Yin Mingzhu

Yin Mingzhu, who played the role of the Spider Queen, was also a famous "modern girl" in Shanghai at that time. She graduated from the Chinese and Western Girls' School, spoke fluent English, and was good at singing, dancing, riding horses, and driving, which made her very comfortable in social circles. The media at that time called her "Miss.FF (FOREIGN FASHION)", which means a foreign-style lady. People who liked her regarded her as a "fashion goddess", while conservative moralists saw her as a rebellious and charming "witch".

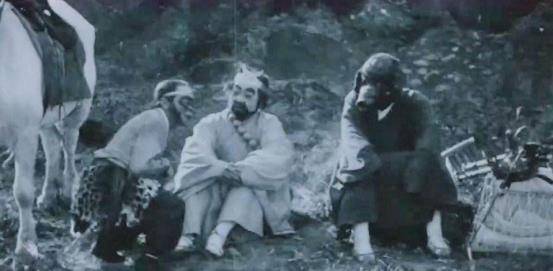

Stills from the movie "Pansi Cave". The three disciples are planning how to rescue their master.

In "Pansi Cave", she actually undressed in public, which must have made some people at the time exclaim "How shameful". But this controversy itself just reflects the ubiquitous dispute between ancient and modern, Chinese and Western in the cultural personality of Shanghai at that time. On the screen, when the spider spirit was burned back to its original form by Sun Wukong's Samadhi True Fire, a line of subtitles was printed on the screen: "Just for a lustful thought, I ended up burning myself for life". This straightforward moral admonition and the previous ambiguous visual presentation seem to have reached a delicate value balance.

Dan Duyu and Yin Mingzhu were the first couple in Chinese film industry. In 1921, Yin Mingzhu was spotted by Dan Duyu and played the leading role in the first love feature film "Sea Oath" produced by "Shanghai Film Company" (founded by Dan Duyu in 1921). Later, she played the leading role in "Ancient Well Waves", "Return to Hometown" and "Family Treasure" directed by Dan Duyu, becoming a movie star. The two fell in love during the filming and got married in 1926. "Pansi Cave" was the first film that Dan Duyu and Yin Mingzhu worked on after their marriage.

The Shanghai Film Company was a family-run film company founded in the early 1920s. It was also called the Dan Family Class, which had a distinct family-run meaning. The main creators of Pansi Cave included first-line stars such as the director's wife Yin Mingzhu, and photographer Dan Gan Ting was also from the Dan family. The young actor who played the centipede spirit's book boy was Dan Duyu's nephew Dan Erchun, who was also one of China's earliest child stars. He played the role of a "melon-eating crowd" in the film. While watching Sun Wukong fight against the monsters, he also did not forget to steal fruits and vegetables on the wine table, which was hilarious. In the end, his true form was revealed, and he turned out to be a petite and cute rabbit spirit.

Photos of the exhibition "Pansy Cave: Journey to the West and Return to the East" at the Jiangnan Branch of the China Film Archive

The professionalism of the actors was also considered in the casting of "Pansi Cave". Wu Wenchao, who played the role of Sun Wukong, was originally a martial artist and later directed "New Pansi Cave" (1940). You can see his fighting scenes in "Pansi Cave". He was very flexible in his hands, eyes, body and steps. He had the posture of the opera stage and the professional background of a dragon and tiger martial artist, which made the powerful Sun Wukong real and credible.

The visual effects of the scenes in "Pansi Cave" also have a mixture of ancient and modern, new and old. Whether it is costumes, props or makeup, they all follow the existing forms of the opera stage. The demons that appear in the wedding scene include the bull-headed and horse-faced demons wearing headgear masks, and the "small painted face" turtle demon master in the opera. There is also a demon commander who borrows the shape of the door god in folk New Year paintings. The fire slave holds an exaggerated large copper hammer and a large razor in his hands, and the spider demon uses mechanical props similar to a marionette after revealing its true form. The visual presentation of the film is a mix of ancient and modern, and the intersection of China and the West, which typically reflects the atmosphere and personality of Shanghai's urban culture at that time.

"Pansi Cave" also tried to restore the bizarre mythological plots in the original work with various film visual special effects that could be done at that time. For example, Sun Wukong's 72 transformations, including using a tuft of monkey hair to transform a group of Sun Xingzhe, required proficiency in the use of specific shooting and post-production darkroom techniques. In the film, the centipede demon was drinking happily and suddenly found a miniature Sun Wukong hidden in the wine. This is the effect of using the perspective principle of the camera that things are bigger when they are near and smaller when they are far away. When the film was developed in the later stage, the distant shot of Sun Wukong and the close-up shot of the wine glass were superimposed. In the early film special effects, French magician and film director Georges Méliès made a lot of contributions. He created many film special effects such as slow motion, fast motion, reverse playback, multiple exposures, superimposition, stop and reshoot, most of which can be found in "Pansi Cave". This shows that in the 1920s, Chinese films were almost synchronized with global films in terms of technology, special effects and craftsmanship.

According to the description of the newspapers and media at that time, the film should have two mythological plots, "Pigsy turns into a fish and plays with the spider spirit" and "Sun Wukong steals clothes with an eagle", but they are completely missing in the Norwegian version. Why is this so? There are probably two possibilities: one is that it was cut when it was released to Norway. The current version is a "single copy" and we cannot find the version released in China at that time for comparison, so we can only guess; another possibility is that these two plots were not filmed that year due to technical and financial conditions. The above media reports were seen in Shenbao at the end of 1926, and the publication time was before the official release of the film. It is very likely that the film producers released the information in advance, but found it difficult to complete the underwater photography, which is a very difficult and risky shooting technique, during the actual shooting.

Stills from the movie "Pansi Cave". Zhu Bajie put his head on the wrong way.

We can also see that many scenes in "Pansi Cave" are out of the original setting of "Journey to the West". For example, Zhu Bajie finally found the chopped-off pig head but installed it in the wrong direction, and a monster turned into a huge chamber pot after it appeared? ! These are not descriptions in the original book, but "private goods" added by the director for the visual effect, entertainment and fun of the film. This makes the visual presentation of the film look a bit messy and even absurd, but it just reflects the cultural landscape of the 1920s where the East and the West, the ancient and the modern, blended with each other, full of the cultural charm of that era.