Note: This article contains spoilers

The relationship between “madness and reason” has always been an important theme in literary and artistic creation. “Madness” can be replaced with terms like “crazy person,” “psychopath,” “deviant,” “maniac,” “outlier,” and “marginalized individual.” Directed by Gu Changwei and starring Ge You and Wang Junkai, the film “Hedgehog,” adapted from Zheng Zhi’s novel “Immortal Disease,” tells the story of a “madman” from an outlier's perspective.

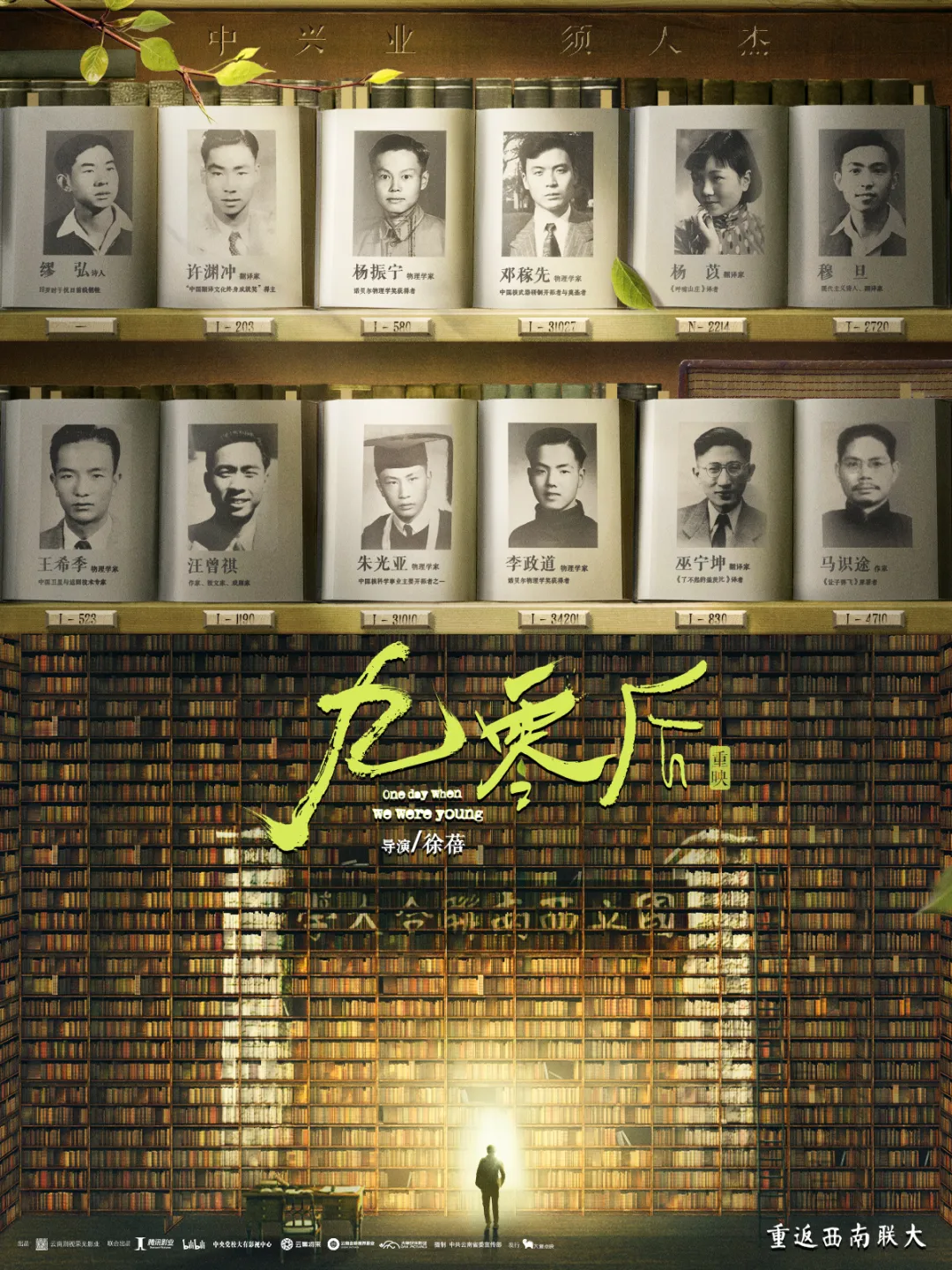

Poster of “Hedgehog”

“I” am the stuttering Zhou Zheng (played by Wang Junkai), seen as an abnormality by others; “my” uncle Wang Zhantuan (played by Ge You) is regarded as a “deviant.”

Wang Zhantuan (played by Ge You)

Zhou Zheng (played by Wang Junkai)

Wang Zhantuan is quite eccentric. He displays unusual behaviors, such as sniffing smoke and directing hedgehogs to cross the street, which carry a sense of absurdity.

He seems to have a form of delusion. He proudly recounts his supposed past as a navy submariner with glorious deeds in the Pacific, which may actually be mere fantasy. He even attempts to imitate the flying fish from “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,” using scallions to try to fly.

He lives life on his own terms. Despite his family's lack of understanding, he maintains a unique lifestyle and does not suffer from internal struggles regarding his mental state.

Wang Zhantuan may appear crazy, yet he often exhibits extraordinary wisdom and rationality.

For example, he possesses exceptional chess skills. He can read while playing chess against others and still win, which indicates his clear thinking ability.

He insists on his identity. For instance, he does not allow “me” to call him “uncle” but insists on using his first name “Zhantuan.” He values personal identity and independence, unwilling to be defined by family relations.

Sometimes, he appears sage-like, deeply questioning social norms and personal experiences. He frequently asks, “That shouldn’t be,” looking bewildered, but in reality, he is questioning the irrationalities around him.

Regardless, both his family and the outside world find it difficult to understand Wang Zhantuan, and he does not seek to win their comprehension. In other words, it is not that mainstream society refuses to accept Wang Zhantuan—his family still loves him; it is that Wang Zhantuan himself rejects adherence to this mainstream system, deliberately choosing not to conform to the “normal” image in society’s eyes.

According to Foucault, “madness” is not a fixed state of illness but a concept that changes with historical and social transformations. Before the Enlightenment, the boundaries between madness and reason were not as distinct as later; sometimes, madness was viewed as a form of special knowledge or supernatural power. However, following the Enlightenment, reason became a social construct aimed at maintaining order and consistency, whereby those who did not meet such standards would be labeled as “mad” or “abnormal” and subjected to exclusion or control, gradually marginalizing them from society.

From this perspective, Wang Zhantuan is neither truly “deviant” nor “mad.” Because he deviates from societal expectations of normal behavior, he is categorized in the “madness” camp and subjected to treatment and discipline from the outside world.

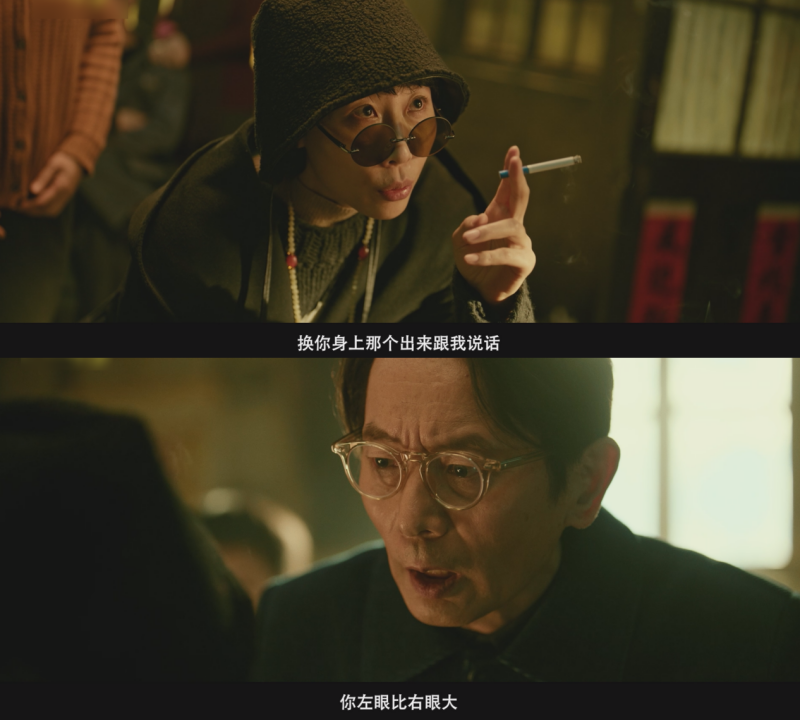

Wang Zhantuan’s family views him as an abnormality that needs treatment, applying a series of control measures, such as his aunt giving him sleeping pills to keep him in a prolonged state of sleep, isolating him from normal social interactions; while Teacher Zhao (played by Ren Suxi) not only embodies certain superstitions or backward views but also showcases the authoritative and oppressive ways society treats “madness.”

Quack Teacher Zhao (played by Ren Suxi)

Wang Zhantuan does not yield. When faced with Teacher Zhao’s bluster and intimidation, he challenges her authority with scornful words and a nonchalant attitude.

Wang Zhantuan deconstructs the so-called “authority”

However, despite Wang Zhantuan's ability to counter oppression, such discipline is still painful. Through “my” perspective, the film embodies this pain.

To treat his stutter, Zhou Zheng is forced to undergo absurd treatments

Zhou Zheng has always been viewed as an “outlier” due to his stutter and repeated failures in school. He often faces ridicule and ostracism from classmates, such as having chalk thrown in his lunch box. Faced with his father’s reproach, belittling, and physical violence, Zhou Zheng's situation becomes even more difficult.

Zhou Zheng suffers bullying at school

Like Wang Zhantuan, Zhou Zheng is equally “stubborn,” and this “stubbornness” comes at a cost. Wang Zhantuan's family is at a loss with him; they can choose to “give up” on him since he is older. However, Zhou Zheng is young, and the outside forces of discipline will not relent. His parents’ love weighs down on him, while Teacher Zhao violently punishes him to the point of making him bleed.

Father (played by Geng Le) berates and beats Zhou Zheng

In Wang Zhantuan’s words, both his and Zhou Zheng’s lives are “stuck.”

What can be done? The struggle between madness and reason does not allow for any kind of peaceful coexistence, as when “madness” exists, its relationship with reason can only be one where the former overpowers the latter.

Thus, Wang Zhantuan is sent to a mental hospital; and Zhou Zheng ultimately becomes a “normal person,” integrating into the order of mainstream society.

The film glosses over Zhou Zheng's transformation. This alteration compared to the novel is somewhat regrettable—this was actually one of the most vibrant segments of the novel. In the novel, Wang Zhantuan faces the forces of discipline with humor; he can accept a life that feels “stuck,” but when it comes to Zhou Zheng, who is at the beginning of life, he cannot bear for Zhou Zheng to follow in his old path.

Therefore, as Zhou Zheng undergoes the painful ritual imposed by Teacher Zhao, Wang Zhantuan, confined indoors, cries out, “You crawl! Crawling over means you become exceptional!”

Zhou Zheng finally speaks, finally submits, finally “confesses,” ultimately being disciplined, and finally crawls towards becoming “exceptional.”

The film’s adjustment, however, feels somewhat “light”—Zhou Zheng secretly slips a phone to Wang Zhantuan, who then calls the police, leading Zhou Zheng to successfully refuse discipline. But how does an outlier who rejects discipline smoothly inherit Wang Zhantuan's dream of becoming a sailor and grow into a respectable adult? This presents a significant logical gap.

In the film, Zhou Zheng refuses discipline; in the novel, he ultimately “confesses”

Regardless, integrating into mainstream social order does not imply that Zhou Zheng is happy. To meet societal expectations, Zhou Zheng has to give up part of his authentic self, embracing externally imposed values and social norms. Although he claims he “will never be stuck by anything” again, deep down, he remains influenced by Wang Zhantuan and his past experiences, and the mental burden of those painful memories has not entirely faded. His words to his mother, “I do not forgive, I cannot forgive,” carry significant weight, but his strength is not derived from always being himself, nor does it stem from truly becoming the next Wang Zhantuan, rather it is that he has become “exceptional”—he has climbed higher than his parents.

“Hedgehog” is essentially a tragic story where “reason” oppresses “madness,” leading to the eventual assimilation of the outlier. When faced with dissent and differences, we often choose to suppress them in the name of reason, rather than attempting to understand and accept. Zhou Zheng’s success, becoming “exceptional” and no longer stuttering, does not bring him the expected happiness; the film conveys an important message: when we attempt to erase individual differences, forcing everyone to live in the same mold, we are, in fact, depriving each person of their uniqueness and sense of happiness.

While “Hedgehog” tells a story set in Northeast China at the turn of the century, compared to the novel, the film somewhat “dehistoricizes” the narrative. In the novel, Wang Zhantuan’s madness relates to his experiences in a turbulent era. This historical context is removed in the film version, resulting in insufficient explanation and support for Wang Zhantuan's character and behavior. Viewers who have not read the novel may find it challenging to fully understand the development of Wang Zhantuan's character. Additionally, due to the lack of deeper connections with the historical context, the thematic criticism of the film feels somewhat weak.

Why is Wang Zhantuan mentally ill? This question is quite crucial

The character of Zhou Zheng does reflect the anger and rebelliousness of youth, but this alone is insufficient for him to integrate into the more complex historical backdrop represented by Wang Zhantuan. The film lightly touches upon the experience of Zhou Zheng's parents losing their jobs, yet they seem to quickly recover from the scars of that era. Their oppression of Zhou Zheng appears to stem merely from parental extremism, rather than any lingering consequences of the time; for example, their job loss creating a deeper obsession with education. Consequently, Zhou Zheng's “I do not forgive” points to individuality, while the era seemingly recedes into the background, making the film's ending feel dull and drawn out compared to the novel.

Despite its flaws, Ge You's performance is truly outstanding. Although “dehistoricized,” today’s audience can easily grasp the core message of “Hedgehog.” The individual growth process is fundamentally a “socialization” process, largely manifesting as a struggle where reason overpowers sentiment, and the collective erodes individuality. Individuals are often encouraged to adopt logical and pragmatic modes of thinking, gradually replacing the more intuitive and emotional understanding from their childhood. Simultaneously, society incessantly imparts mainstream values and behavioral norms to individuals, who must gradually learn and adapt to the social rules and cultural customs. Thus, the growth process inevitably involves conflicts and harmonization between individuality and societal expectations, and feeling “stuck” is a common life experience.

“From now on, I will never be stuck by anything,” may be an unrealistic aspiration. Even a free-spirited Wang Zhantuan feels trapped and is forced to escape the asylum; what about us? Yet the significance of the film lies precisely here: it challenges existing notions and social norms, encouraging us to discover and ponder those issues that may be overlooked or left unspoken in daily life, calling for us to embrace differences, accept others, and collectively reflect on or resist those oppressive forces masked as reason or purportedly for our own good. The influence of cinema need not be immediate; it can be subtle and profound.