In the film and television industry, screenwriters are like behind-the-scenes magicians, creating vibrant story worlds with their words. They are the starting point of all films and shows, the first link in the filmmaking process. But do they have enough voice in the industry? Are they truly given the respect they deserve? Or, in an industry process that is complex and hard to define, do screenwriters become the scapegoats, the ones blamed without recognition for their contributions?

Wang Xiaoqiang is a prominent screenwriter in recent years, with works that span various genres and showcase his rich creative talents. High-quality series such as "The Mask," "The Rival," and "The County Committee Compound" have all come from his pen. Through years of practice and accumulation, he has developed a unique understanding of the screenwriting profession.

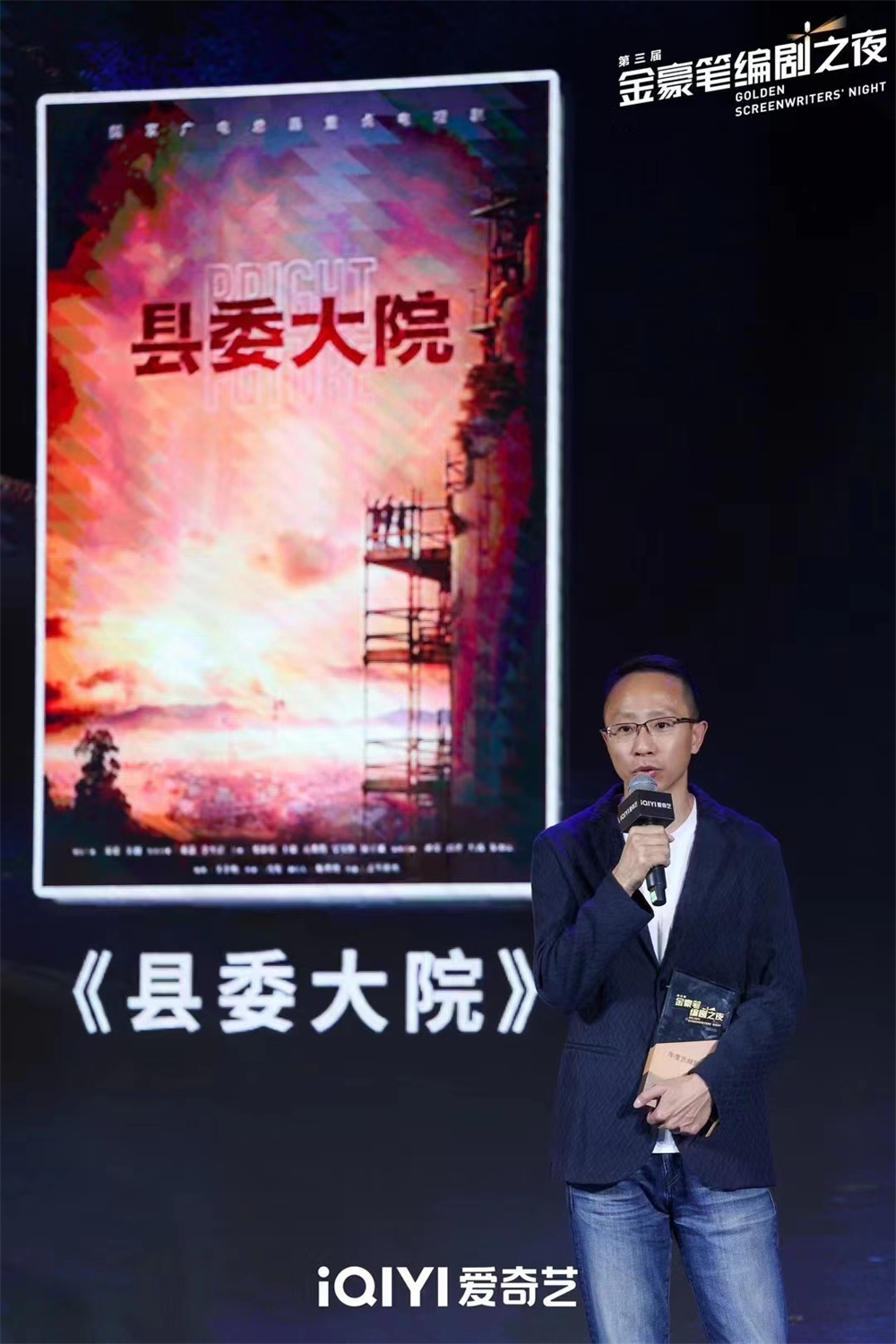

In 2013, screenwriter Wang Xiaoqiang received the Annual Contribution Script Award for his TV series "The County Committee Compound" at the Third iQIYI Golden Pen Night.

For instance, when discussing a poorly received show, screenwriters often find themselves in the position of scapegoats, a notion Wang Xiaoqiang expresses understanding toward. He believes that the process of making a TV series involves numerous stages—from the initial writing by the screenwriter to the director's reinterpretation, performances, editing, review, and distribution—resulting in a final product that may differ significantly from the original script, changes that are often beyond the screenwriter's control.

He candidly admits that collaboration between departments during production often resembles a "arranged marriage," where the screenwriter has limited options. Therefore, finding partners who share similar worldviews, aesthetics, and mutual respect is crucial.

Moreover, we also discussed the issues surrounding the voice and status of screenwriters. Wang Xiaoqiang pointed out that while the industry's regard for screenwriters has increased, and most professionals are aware of the importance of screenwriters and scripts, in practice, respect for screenwriters remains at the level of "awareness."

Wang Xiaoqiang’s insights may provide a glimpse into the complexities and significance of a screenwriter's work and encourage audiences outside the industry to adopt a more rational perspective on the world of screenwriting, paying attention to their efforts and contributions.

On June 26, 2024, at the 29th Shanghai Television Festival, Wang Xiaoqiang attended the Baiyulan Award judges' meeting.

【Dialogue】

Pioneer News: Is there a trend towards ensemble casts in global film and television? What do you think?

Wang Xiaoqiang: From my own observations, ensemble dramas are indeed a creative trend both domestically and internationally. Whether it’s the density of the plot or the complexity of character relationships, I believe ensemble dramas are the way to go. Nowadays, audiences or the market are no longer satisfied with the linear storytelling and simplistic character relations of the past. For screenwriters, ensemble shows pose a greater challenge. Humans are multifaceted and rich in nature, and if screenwriters can address these complexities in their narratives, it provides a better foundation for actors' performances and the director's reinterpretation. If the nutrients are richer, the produced fruits could be more vibrant, and the flowers more magnificent. If the initial soil is thin, it may yield little in return.

Pioneer News: How can we succeed in writing mainstream narratives?

Wang Xiaoqiang: We often refer to the term *mainstream narrative*, but I believe there is no strict distinction between mainstream and non-mainstream. At one point, the term began to carry a negative connotation, primarily because mainstream works often exhibit stereotypical issues.

When I wrote "The County Committee Compound," I regarded it as an industry or profession drama. The individuals in the county committee are just like anyone else in their profession; they go to work every day, experiencing their own joys and sorrows. It's important to understand this group at its core, to know as much as possible about their relationship with their work, such as whether they love their jobs, whether it is voluntary or forced, and whether their roles bring them honor or shame. The more thoroughly you grasp these aspects, the more helpful it will be for shaping the story and characters.

If time is too short, interviews can be fruitless for screenwriters. Sometimes, it’s better to shadow prototype characters for three days to observe closely. For example, if you interview a deputy county head, claiming to be a screenwriter, he might "translate" his responses, uncertain of how you will portray him in your show. In such cases, gaining trust quickly becomes challenging; it’s more effective to quietly observe how he interacts with different people—superiors, subordinates, family, parents, children, and partners. Overall, the more comprehensive and detailed the understanding of the interview subject, the smoother the writing process will be.

Still from "The County Committee Compound"

Pioneer News: Can you share a specific example of how you closely observe a subject, including those around them?

Wang Xiaoqiang: A very simple example is when I went to the emergency department of Beijing’s Third Medical University Hospital to experience life, as I was writing a medical-themed piece. I followed a night-shift doctor; the hospital sees a high volume of patients every day. If I were to bombard him with questions, he wouldn't have time to respond, and he might also "translate" his thoughts. The objective conditions often don’t allow for continuous questioning, so I found it much better to quietly observe, for instance, the doctor-patient relationships and his communication with family members of different personalities.

During my shift observation at the hospital, I encountered a patient around 70 years old, suffering immensely, repeatedly bumping his head against the wall due to his headache. His daughter was anxious, repeatedly urging the doctor to help her father immediately. The doctor explained, “There’s a patient over there—a woman who drank alcohol after taking ceftriaxone, and she’s in critical condition.”

This scene left a lasting impression on me. Had I not gone to experience this life firsthand and only thought about it at home, I would have imagined that doctors would panic when an elderly patient arrives. Yet, witnessing that situation made it clear—when faced with multiple patients needing urgent attention, a doctor must maintain composure, make tough decisions, prioritizing those in life-threatening situations. The agony of one patient may require them to wait, a realization that challenges many people's perceptions of emergency doctors.

Cover of the novel "Crazy Hospital"

Pioneer News: Many platforms are now calling for cost savings while raising the bar for genre-specific works. They often find it hard to feel excitement about a specific genre and usually require screenwriters to explain the “breakthrough point” behind the story. How do you, as an experienced screenwriter, identify these breakthrough points while creating your stories?

Wang Xiaoqiang: For me personally, when confronted with such issues, the slogan and theme might not hold much significance. What is crucial is identifying a storytelling approach and character relationships that differentiate my narrative from similar works in the market.

For example, when writing a contemporary National Security Bureau drama, I must find a unique narrative angle. In writing historical espionage tales, given the competition in the genre—including several crime dramas—it’s crucial to innovate and find fresh perspectives. An abundance of medical dramas means I face a similar challenge; it could take considerable time to discover a unique angle for my narrative. Once I find that, the subsequent efforts often yield far greater returns.

Still from "The Rival"

If approached the other way, forcing a story or script out of thin air without clear concepts can lead to a struggle, having to exhaustively drill down into finding a slogan or theme from an unoriginal narrative angle or character relationship, then artificially telling the platform, “This is different too.” In reality, I believe it is more vital to develop a new set of character relationships. For some time, the reference to historical espionage often involved fake couples. However, with "Lurking" having gained a strong foothold in people’s minds, writing yet another fake couple scenario becomes exceedingly difficult; it would demand a lot of energy and effort. Thus, I think that in different types of stories, screenwriters face the biggest challenge in racing other creators in similar genres, figuring out how to be faster, more graceful, and do it in a shorter timeframe. Every screenwriter likely has their own methods in this regard.

Poster for "The Mask"

Pioneer News: There has been much discussion this year about the use of AI technology in the film and television industry. Currently, it has made significant impacts on the middle and later stages, but it has yet to disrupt screenwriters. Have you attempted writing with AI? What do you think about its development potential and its impact on screenwriting?

Wang Xiaoqiang: My experience regarding AI's influence on screenwriting has gone through several phases of psychological change. At first, I shared the common anxiety among the public, fueled by self-media that often spread panic, claiming that everyone was at risk of unemployment, with screenwriters being the first group affected, as logically, AI seemed capable of replacing screenwriters or at least a significant number of them.

Furthermore, I had previously studied medicine, specifically medical imaging—many male graduates go into CT, MRI, or radiology. I have a senior sister who still works in that field; I learned that hospitals in Beijing annually select some imaging specialists, particularly heads of ultrasound departments, to compete with computers—or one could say, AI.

I found out that AI is incredibly powerful; for instance, if you have 20 experienced doctors, each needing four hours to analyze 100 images and write reports, AI could do this in just 10 minutes, with human error rates around 30%, compared to AI's possible 10% or 15%. Moreover, AI requires no breaks, no salary, and no complaints about management. Initially, I was quite influenced and impressed by the strength of AI.

However, through subsequent discussions with fellow colleagues in the industry and friends involved in tech and AI, I gradually realized that for the art industry, at least for now—likely for a long time to come—AI serves as an excellent tool. I believe in the future, screenwriters who adeptly utilize AI will have a very capable assistant who understands them well. Will there come a day when AI develops its consciousness? If that day arrives, it would not be a problem limited to screenwriters.

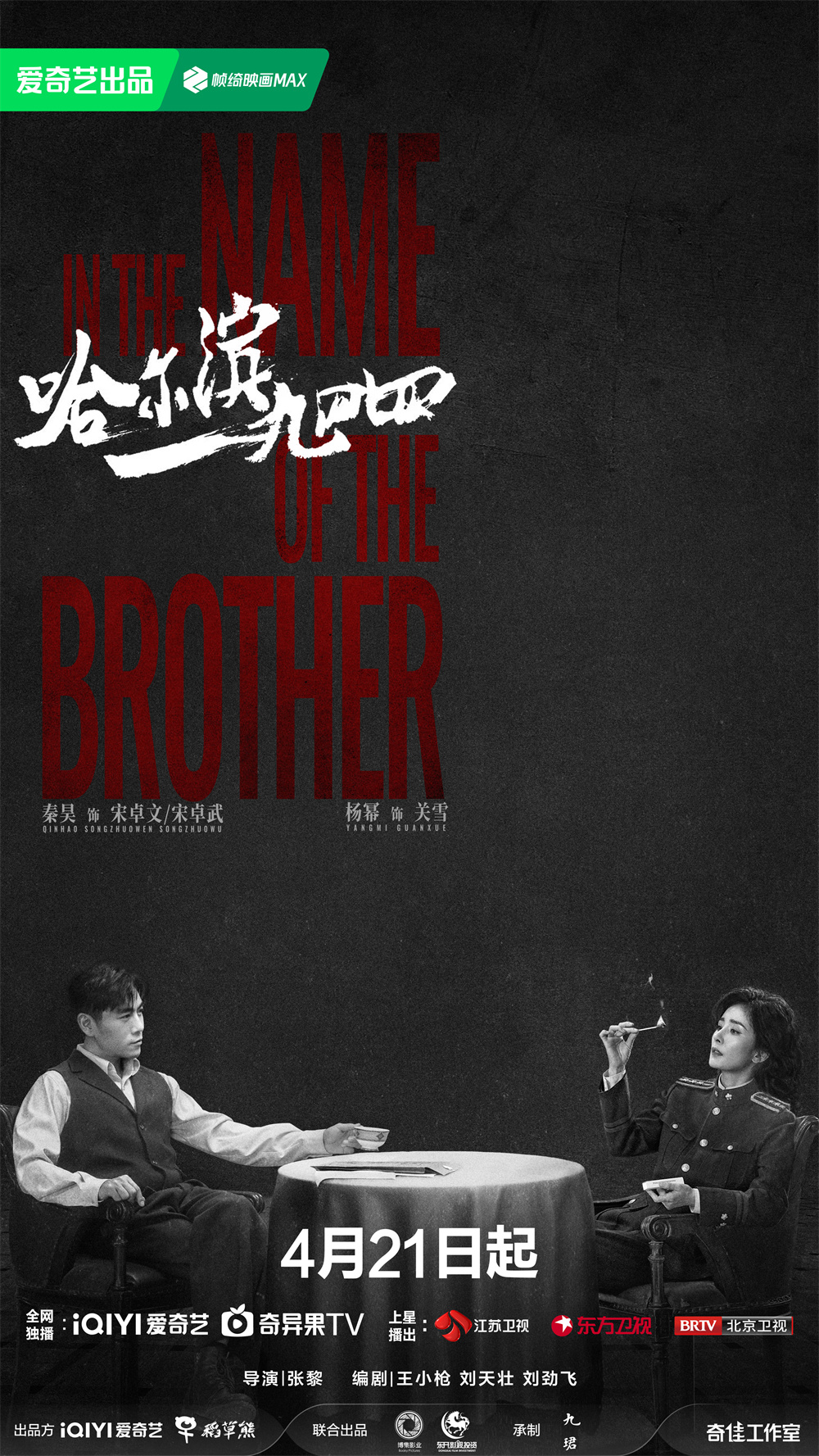

Poster for "Harbin 1944"

Pioneer News: When a show performs poorly, many attribute the primary issue to the screenwriter, often making them the biggest scapegoat.

Wang Xiaoqiang: Hearing this question, I couldn’t help but sit up straighter. In fact, when I was younger, say a decade ago, I frequently felt anger due to pessimism, experiencing loss of control, and expressing those feelings online. However, I have matured a bit since then.

I believe a project undergoes many stages from the moment a screenwriter writes the first word to the completion of the film, undergoing the director’s reinterpretation, performances, editing, review, and distribution until it finally airs. The degree to which it aligns with the original script is hard to manage, and many changes may occur throughout the process. In my experience, I now prefer collaborating with directors I've worked with and who understand me, as this attracts fewer friction points. Of course, some sweet friction can be beneficial, while other times it can be wholly detrimental.

Returning to the screenwriter-director relationship, it’s akin to a marriage; the industry features a unique trait where screenwriters and directors often resemble previously arranged marriages. Once it’s established that I’m the screenwriter and a director joins the project, we often don’t know each other well enough and must "marry" before finding common ground. Throughout the process, we might realize our values clash, but there’s little room for change, and we might have to grit our teeth and see it through, with limited chances for