The 30th Sarajevo Film Festival successfully took place from August 16 to August 23. Romanian director Emanuel Pârvu's film Three Kilometers to the End of the World won the top honor, the "Heart of Sarajevo" for Best Film. In addition to the trophy, the production team received a cash prize of €16,000 provided jointly by the festival and the Sarajevo Tourism Association.

Emanuel Pârvu's Three Kilometers to the End of the World wins the Best Film award

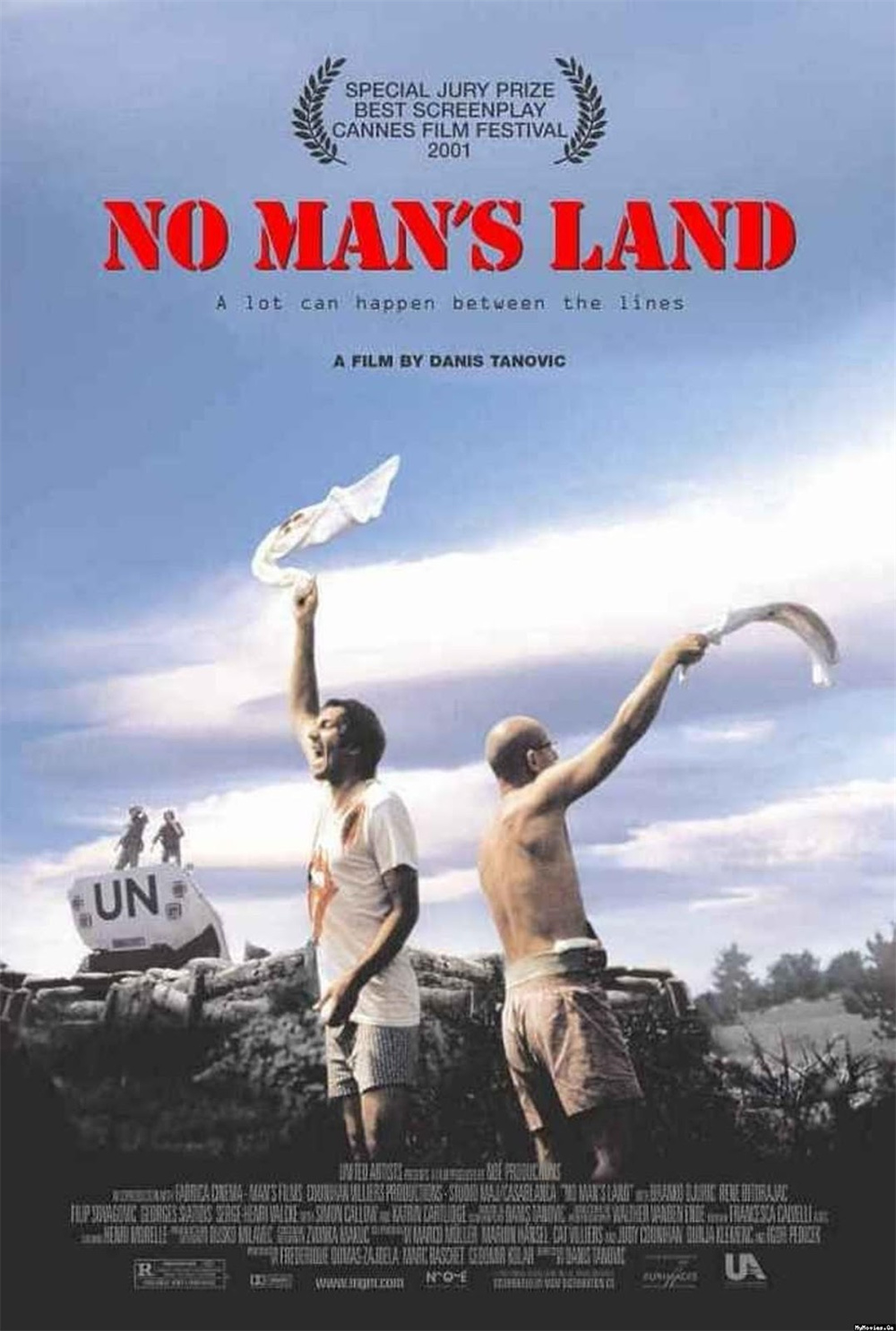

This year's Sarajevo Film Festival jury chair was renowned American screenwriter and director Paul Schrader. The jury also included Slovenian actor Sebastian Cavazza, Bosnian director Jasmila Žbanić, Finnish director Juho Kuosmanen, and Swedish actress Noomi Rapace. The opening film of the main competition was the new movie My Late Summer by Bosnian director Danis Tanović. Tanović's film No Man's Land won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 2002, and he has also received two Silver Bear awards at the Berlin Film Festival for A Forgiveness (2013) and The Death of Sarajevo (2016).

Danis Tanović's acclaimed film No Man's Land, set against the backdrop of the Bosnian War

A Full Cinema in Wartime

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Sarajevo Film Festival, a poignant milestone reflecting on the past. The festival's origins trace back to 1995 during the turbulent Bosnian War, aiming to provide a glimmer of hope to the citizens of Sarajevo, who had been under siege for four long years. The Bosnian War erupted in 1992, leading to Sarajevo becoming a besieged city. Bosnian Serb forces refused to join the newly independent Bosnia and stationed over 13,000 soldiers in the surrounding hills, unleashing bombings on the city using tanks and artillery, while the poorly equipped Bosnian Army struggled to defend itself. In April of that year, Serb forces partially sealed off Sarajevo, isolating it from the outside world, marking the longest urban siege in modern European history.

From April 5, 1992, until February 29, 1996, over 10,000 people lost their lives in Sarajevo, the majority of whom were civilians. Additionally, due to escape routes like underground tunnels, by 1995, the city's population had declined to about 60% of pre-siege numbers. Despite the dwindling population and deteriorating living conditions that had worsened since the war began in 1992—exacerbated by frequent power cuts—the Sarajevans' passion for culture and cinema remained unshaken.

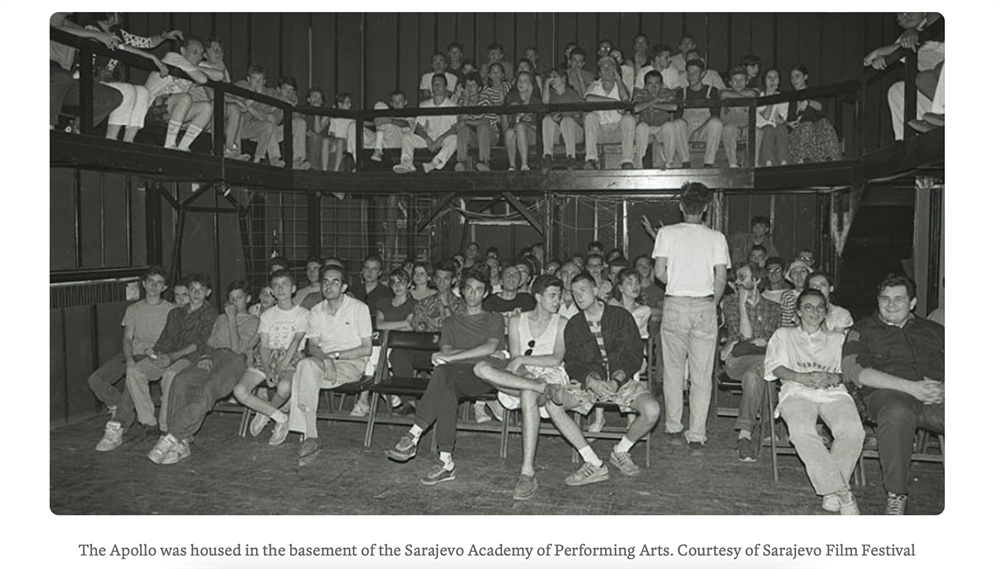

The Apollo Theater, located in the basement of the Sarajevo Academy of Performing Arts, once served as the headquarters for the Obala Art Center that emerged in the 1980s. Its founder, Mirsad Purivatra, who would go on to serve as the festival's artistic director for many years, remained undeterred by the war, continuing to run his cultural venture in the Apollo Theater.

The Apollo Theater is located in a basement rather than being a typical cinema.

Mirsad Purivatra, founder and artistic director of the Sarajevo Film Festival

Even though Sarajevo was under siege, United Nations peacekeeping forces managed to provide limited assistance, allowing some supplies and personnel to enter the city via established channels. During those years, Purivatra, affectionately nicknamed "Miro," leveraged his network to bring renowned artists like photographer Annie Leibovitz through the frontlines to hold various art exhibitions at the Apollo Theater; he also welcomed prominent intellectual Susan Sontag during her visits, inspiring the citizens of Sarajevo. However, compared to exhibitions and theater performances, restoring the infrastructure for film screenings was significantly more challenging.

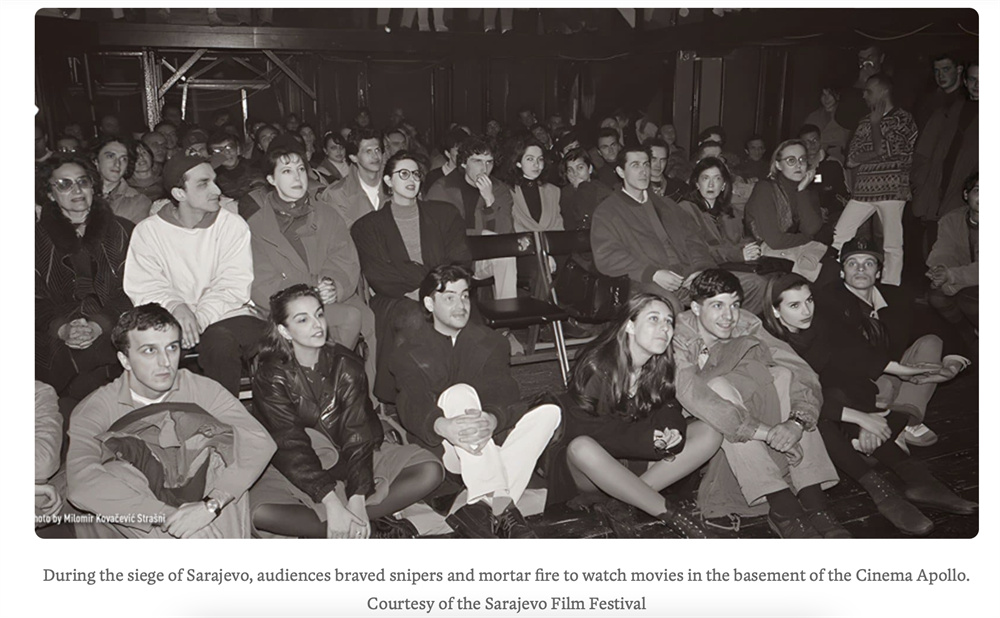

Those who defied the war to watch films at the Apollo Theater.

One day, a team of UN peacekeepers arrived at the performing arts academy with a generator. With the academy's only functional projector and the limited film stock available in the library, the first public film screening since the siege commenced kicked off. "The audience's reaction is something I'll never forget," Purivatra recalls. "It allowed them to momentarily escape from the daily terror, tragedy, and fear, even if just for a short while." That night, he resolved to make the screenings a regular event because "film helps us survive."

News of the underground cinema spread quickly through word of mouth. Initially, they screened just one film a week, but soon audiences requested more showings, leading Apollo Theater to host screenings every night, followed by discussions. As Purivatra puts it, "In the face of bombings and snipers, we discovered that survival requires more than just food and warmth. How do we survive spiritually? That requires culture and art."

Film Artists from Everywhere Share Their Gifts

Initially, admission to the Apollo Theater was entirely free, but as nightly screenings became regular, the organizers began to charge an entry fee of one cigarette per person, a token contribution as the cinema technician—a heavy smoker—needed them. Cigarettes had become a scarcity after the siege began. Furthermore, as regular screenings commenced, sourcing films became a challenge since the library's video cassette collection was limited. Fortunately, with the help of foreign war correspondents, word of the Apollo Theater quickly reached film enthusiasts around the world.

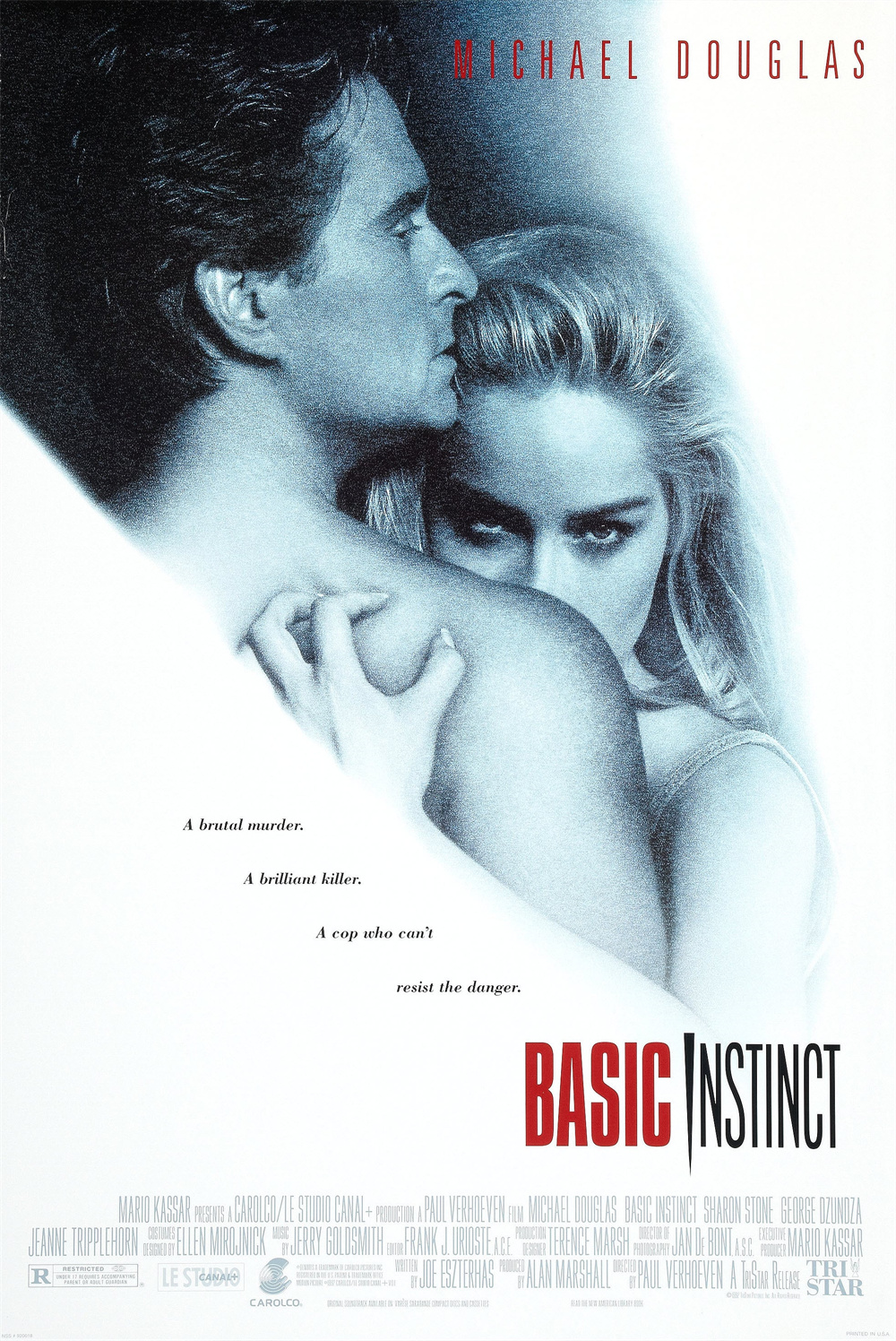

Oscar-nominated American writer and director Phil Alden Robinson sent Purivatra over 100 brand-new video cassettes, which included his award-winning film The Dream Team produced by Universal Pictures, along with new releases from Carolco Pictures, including Basic Instinct. Purivatra recalls that the video of Basic Instinct was screened at the Apollo Theater for 30 consecutive days, attracting unprecedented crowds.

Basic Instinct screened at the Apollo Theater for 30 days

Scottish producer Mark Cousins also extended a helping hand. At the time serving as the curator for the Edinburgh Film Festival, he was part of a European cultural delegation. Under UN peacekeeper protection, he flew military transport from Zagreb to Sarajevo and then traveled in an armored vehicle through war-torn areas to reach besieged Sarajevo. He brought with him newly released video cassettes including Ken Loach's Sweet Sixteen, documentary Osaka Story by Nobuhiko Obayashi, and Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry. Before the screening, Cousins excitedly expressed in front of an audience of more than 120, "Coming here feels like crossing an entire universe. The Apollo is not the biggest cinema I've seen, but because of what it represents, I think it is the most beautiful cinema in the world."

Ken Loach's Sweet Sixteen

Later, renowned film festival curator Marco Müller, then the artistic director of the Locarno Film Festival, was also moved by the spirit of Sarajevo's residents. He carefully selected a group of films, including all the award-winning entries from that year's Locarno Film Festival, and traveled to the war-torn city. "We were told to fly to Zagreb and wait for instructions," Müller recounted, "so we brought two backpacks filled with video cassettes and arrived at Sarajevo Airport." However, UN peacekeepers denied them passage on their military flights, and the two were unceremoniously ejected from the airport late at night, ending up stranded in a snowy square several miles from Sarajevo.

After nearly an hour, they managed to flag down a Ukrainian tank. Müller recalls using his "very poor Russian" to persuade them to let them ride into the city. "It was during what was known as a cease-fire, but snipers on the hills sometimes fired at night." In darkness, Müller and the Ukrainian soldiers entered the snow-covered city. "To reach the theater, we had to go through a system of underground tunnels. I was stunned to find the theater full, and everyone was dressed up. Suddenly, it became clear to me why watching films here was so important to them, as it offered them the hope of returning to normal life."

A Spark

From that cold, bleak night in February 1993, when the first underground screening took place, the Apollo Theater operated continuously for nearly three years until the war's end. In 1995, the first light of peace appeared. One night, Purivatra sat outside the theater with Marco Müller, discussing the future of the wartime cinema after the war.

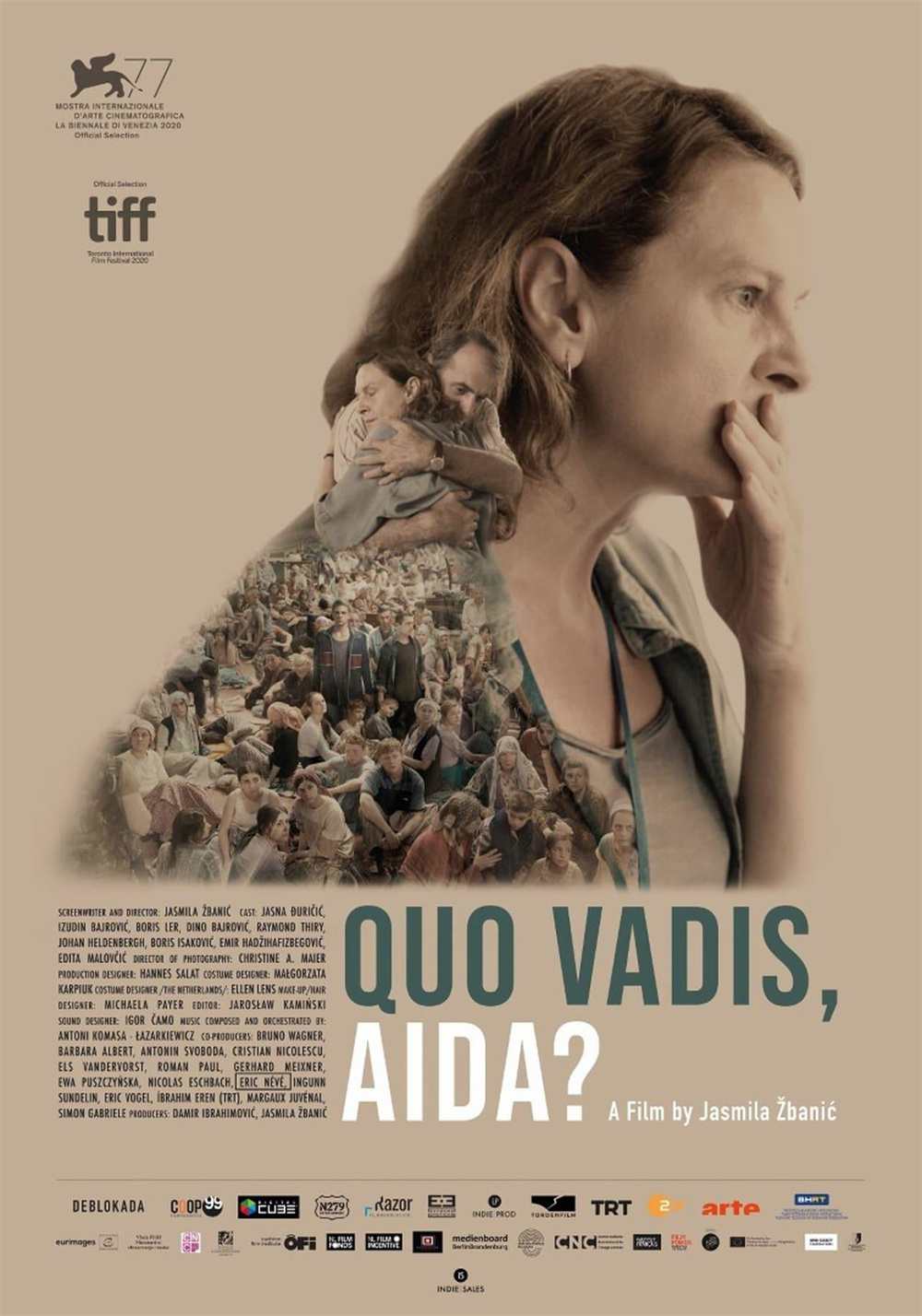

Both men aspired not only to preserve the passion for film fostered by underground screenings but also to support a new generation of Bosnian filmmakers, including Danis Tanović and Yasmila Žbanić, who would later receive Oscar nominations for their poignant works showcasing daily life during the siege of Sarajevo. "We hope to find ways to facilitate the rebirth of Bosnian cinema and create an event that serves as a bridge between Sarajevo and the rest of the world," Purivatra stated.

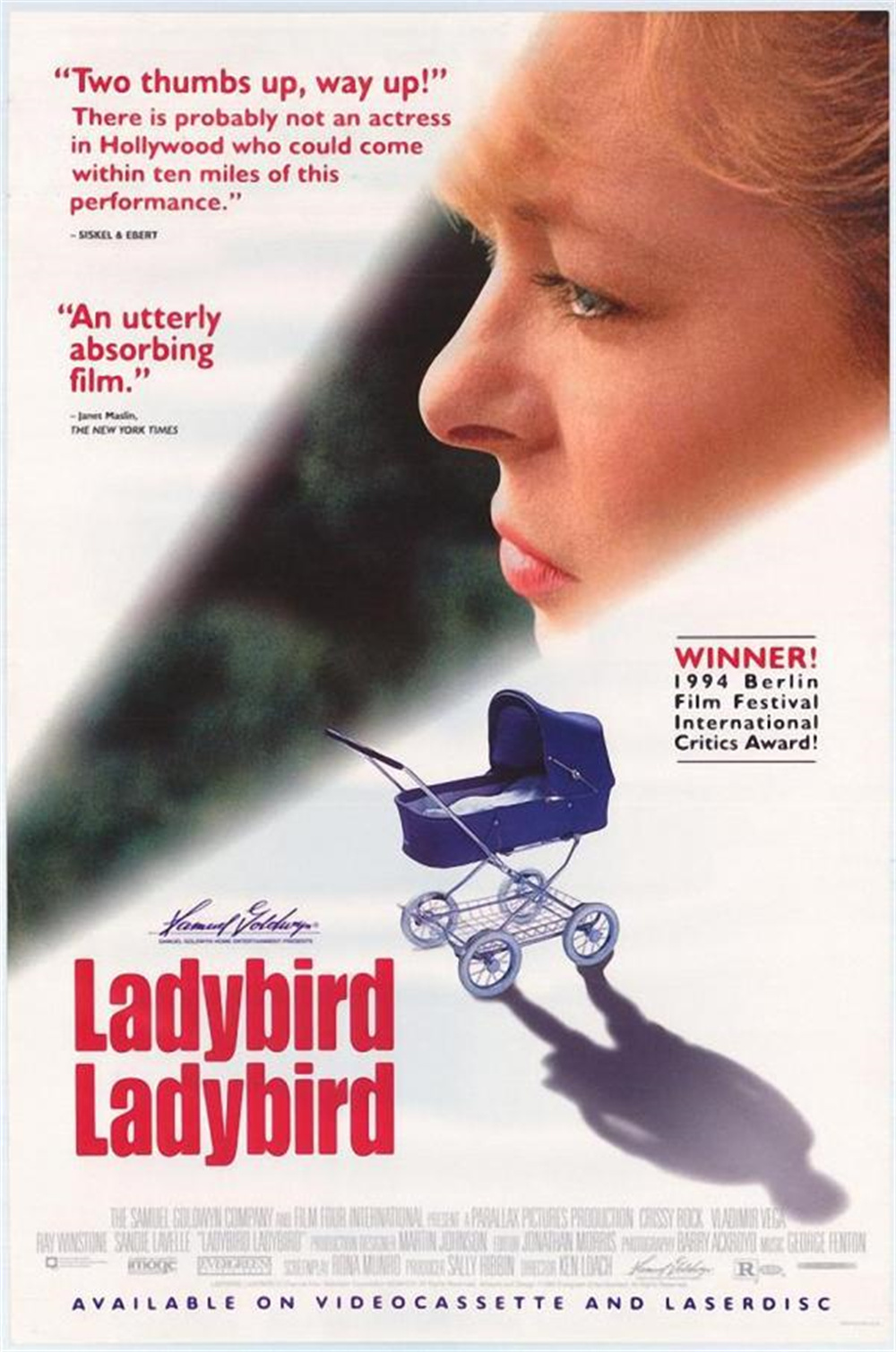

Yasmila Žbanić's Quo Vadis, Aida?, set against the backdrop of the Bosnian War

The first Sarajevo Film Festival was initially scheduled for the summer of 1995, but the intensifying conflict forced the organizers to postpone it to the fall. Shortly thereafter, the Dayton Accords were signed, bringing an end to the devastating war.

In the days leading up to the first Sarajevo Film Festival, 17-year-old Elma Tataragic heard that they were looking for someone with good English skills to help with outreach, so she went to apply. Today, 30 years later, in addition to writing scripts, she still works there and is now the head of the competition section of the Sarajevo Film Festival.

When the war first broke out, Elma was just 16, and in her own words, she "longed to escape, to flee the war, even for just a few hours." At that time, she learned about the Apollo Theater and decided to go see a film despite her parents' objections. "I was young; I wanted to live normally. My parents begged me not to go, and my father even knelt down to plead with me, but I didn't listen. I rode my bike to the Apollo. It was indeed dangerous, passing by sniper positions, but I didn't care. I was so excited; I wore my best clothes and even remember wearing white sneakers. Those shoes were new and pinched, but I didn't mind. The first movie I watched there was Whitney Houston's The Bodyguard, followed by a week of French New Wave films. Honestly, I didn’t care what I watched; I just wanted to see films and escape for two hours into another world, away from the terrible things happening around us every day."