“When a ship sinks to the bottom of the sea," is the first line of the theme song of the film "The Lisbon Maru."

In 2014, producer Fang Li and director Han Han were filming the movie "The Lisbon Maru" on Dongji Island when they unexpectedly heard local fishermen recount a story about a World War II wreck nearby. As a “science guy” who graduated from East China Geological Institute (now Donghua University) with a major in Applied Geophysics, and having previously worked in system integration and R&D of earth detection and marine survey technology before entering the film industry, Fang Li was curious and led a marine technology team to conduct surveys in 2016.

This ultimately sparked the story behind the film "The Lisbon Maru Sinking," which premiered on September 6 of this year.

Poster for "The Lisbon Maru Sinking." All images in this article, unless otherwise credited, are provided by interviewees.

Returning to the historical scene: At the end of September 1942, 1,816 Allied prisoners of war were confined in the hold of the Japanese armed transport ship "Lisbon Maru," sailing from Hong Kong to Japan. As the Japanese military violated the Geneva Convention by failing to display any flags or markings to indicate the transport of POWs, the Lisbon Maru was struck by a torpedo fired from the US submarine "Sculpin" three days into its smooth voyage.

Still from "The Lisbon Maru Sinking."

In the 25 hours from when the ship was hit until it sank, the Japanese military locked all the British POWs in the lower hold, nailing shut the hatches with wooden planks and canvas. The British prisoners fought bravely to escape. In a dire moment, fishermen from Zhoushan, Zhejiang risked their lives to row out in small boats and rescued 384 barely alive Allied POWs, providing them with food, clothing, and shelter. Nevertheless, 828 POWs either drowned, were shot by the Japanese, or were trapped inside the ship and could not escape.

“From the moment I learned about this event, my curiosity led me to lead the exploration to find the wreck. After locating the ship, I wanted to identify people connected to it and understand their stories, what they went through 82 years ago. That’s how this story was uncovered. Now, it's time to share it with more people,” Fang Li said during an exclusive interview with The Paper.

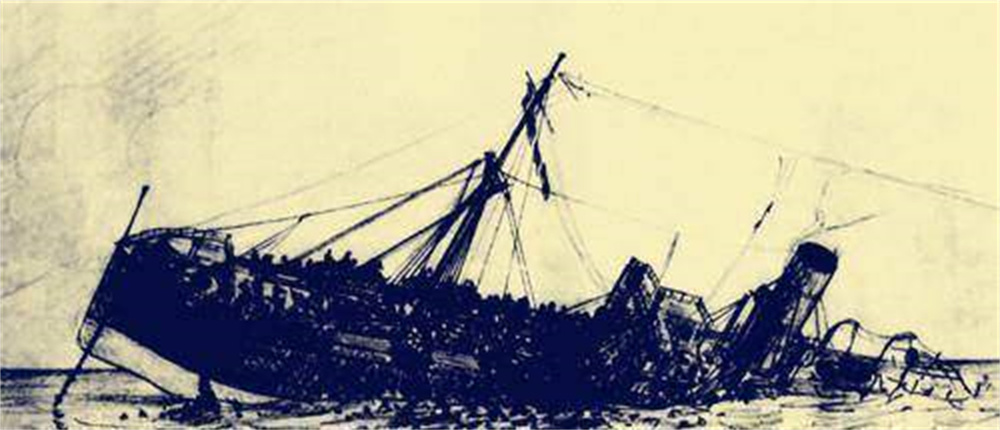

The Lisbon Maru Sinking.

From the initial idea to film "The Lisbon Maru Sinking" to its release on the big screen, it took a full eight years. What has Fang Li, the director of this film, experienced throughout these eight years? This will be presented comprehensively in the following conversation. Fang Li has stated more than once to reporters that this is the most important thing he has done in his life. “I’ve thought seriously about it—if I don't do it, then who will? No one else understands underwater imaging, search, and investigation along with filmmaking like I do. Although I had never made a documentary before, I at least know what images mean. So I kept telling myself, it’s destined for you to do it; if you don’t, you're a historical criminal.”

His earnest and solemn expression is reminiscent of when he once knelt in a dramatic plea for screening rights to Wu Tianming's posthumous work "The Morning of the Birds."

Director and producer Fang Li.

[Dialogue]

“There’s a difference of as much as 36 kilometers between the actual wreck location and the historical coordinates.”

The Paper: I know that beyond being a filmmaker, you are also a geophysicist and maritime technology expert. Can you first introduce from a technical standpoint why the Lisbon Maru was not detected from the time it sank in 1942 until your team confirmed its location in 2017, a span of 75 years? From the film, we understand that it sank in waters just over 30 meters deep near Dongji Island—while the Titanic sank to 3,700 meters in the North Atlantic. Over 30 meters is a depth that professional divers can reach without equipment. What hydrological and geographical reasons, and technological developments, account for this?

Fang Li: The inability to find it was not related to water depth but rather to the incorrect flat-plane coordinates. First, it’s important to note that human navigation systems, such as GPS (Global Positioning System) and China's independently developed Beidou positioning system, only emerged in the last few decades, allowing us to accurately locate ships and aircraft in transit. During World War II, however, navigation relied on sextants—a technology that dated back to the 18th century and often resulted in significant errors.

The previously reported coordinates of the Lisbon Maru shipwreck were mentioned in the historical advisor Tony Banham's book "The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain's Forgotten Wartime Tragedy." He derived them from historical records kept by the Japanese. This book was published by the University of Hong Kong Press around 2005, and it was then that people began to pay attention to the Lisbon Maru sinking incident. Tony lives in Hong Kong and, together with Shen Jian, organized a local research group on the Lisbon Maru. They once invited a survivor from the ship to return to Dongji Island, where they used a fish finder, a relatively rudimentary sonar device, to search the local waters. Phoenix TV reported on this event, but they were unsuccessful in locating the wreck. This was because the true location of the wreck, which is “30°13'44.42"N 122°45'31.14"E,” was 36 kilometers away from the coordinates recorded by the Japanese military.

Historical advisor Tony Banham.

The Paper: So how did you and your team find the wreck in 2016?

Fang Li: Dongji Island is not a single island but a group of four small islands: Miaozi Lake Island, Qingping Island, Dongfushan Island, and Huangxing Island. We conducted our search by renting a ship and installing specialized sonar equipment. At that time, we scanned a 400 square kilometer area in the sea around Qingping Island and found a large sunken ship after spending more than half a month searching. However, sonar uses the principle of sound wave reflection to determine the shape of detected objects based on the reflection from their surfaces, and it cannot ascertain their material. So we still needed to ascertain whether this was a steel ship or a wooden one. The next step was to prove this shipwreck was indeed the Lisbon Maru, which prompted us to return in 2017.

To identify the wreck, the best method would be to send divers or underwater robots down to see for themselves, to visually confirm the hull number right away. But as I mentioned earlier, Zhoushan is known as the “City of a Thousand Islands,” and Dongji Island includes four small islands. With so many islands, the seabed is uneven, and the complex local marine conditions, due to colliding currents, make the water particularly turbulent, prone to forming various chaotic flows and vortices, which divers fear the most. In maritime terms, the speed is measured in “knots,” where one knot equals one nautical mile per hour. Humans can swim against a maximum of one knot of current; at two knots, it's futile; at three knots, they will be swept away and go with the flow. In the waters around Dongji Island, the flow speed is nearly at three knots nearly year-round, making it extremely dangerous for divers to attempt entry. In September 2017, we arrived with full air, surface, and underwater equipment and didn't even dare to let divers enter the water, as the underwater robots we sent were swept away.

The Paper: Since you couldn't rely on divers or robots for firsthand verification, how did you determine the identity of the wreck?

Fang Li: There were indeed ways, and that was precisely my expertise. We employed methods from two fields: first, geophysical exploration. The Lisbon Maru being a steel ship, we could confirm the physical characteristics of the ship using magnetometers. A helicopter equipped with a magnetometer flew extremely low; this is similar to how military anti-submarine aircraft search for submarines. Earth's magnetic field is uniformly distributed from the North Pole to the South Pole, so if a significant magnetic anomaly appeared below the surface in the sea, it indicated a large magnetic object was present. At that time, the magnetometer detected peak readings of 800 nanoTesla, which indicated it could be a structure made of several thousand tons of steel, approximately matching the 7,000-ton capacity of the Lisbon Maru.

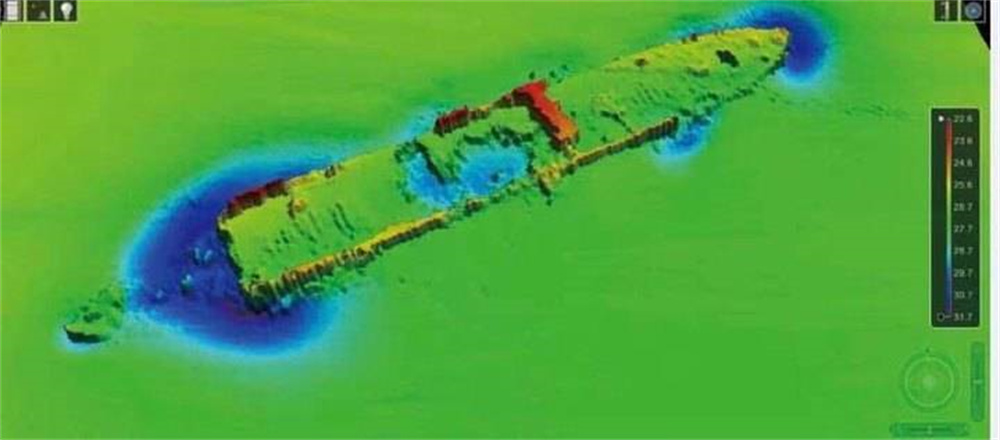

We used an unmanned survey vessel equipped with sonar to conduct detailed scanning and imaging of the wreck—back in 2016, imaging was performed on a manned vessel, and the resulting images could only provide a general idea that it was a sunken ship, rather than a large rock. When humans maneuver vessels at sea, the water is supple, and even the best helmsman can only maintain a general straight course, leading to distortion in the images obtained. The unmanned survey vessel is steered by a computer and can correct its course via GPS every second, which is far quicker than human reaction time and results in a relatively straight course, providing more precise imaging. Based on the latest imaging data, we compared its geometric dimensions to historical construction blueprints and ultimately confirmed it was indeed the Lisbon Maru.

In 2017, Fang Li's team accurately scanned and imaged the location and underwater three-dimensional shape of the Lisbon Maru wreck.

The Paper: You have previously participated in the design and construction of deep-sea manned submersibles and certain types of naval deep-sea rescue vehicles; you must also understand and master the necessary techniques for underwater salvage. Why didn't you consider recovering some artifacts from the Lisbon Maru? Wouldn’t these artifacts, if brought to light, enhance the documentary's narrative and impact?

Fang Li: This question is quite complex. The Lisbon Maru was a Japanese ship; post-World War II regulations stated that related Japanese military assets were to be taken over by the US military, and it sank in Chinese territorial waters where the victims were all British soldiers, leading to blurred diplomatic jurisdiction.

From an engineering perspective, the shipwreck, being so long submerged near the continental shelf, has severely corroded and decayed. Moreover, over the 70 years, the trawlers of local fishermen have passed back and forth over the wreck, leading it to become coated in fishing nets. In 2019, the National Cultural Heritage Administration's underwater archaeology team came to conduct exploration, and we provided many pieces of equipment. They camped on the wreck for a month and attempted to winch the fishing nets, but despite tons of pulling force, they couldn’t budge. Sending divers down to recover artifacts would be hazardous due to the strong currents, and if they got caught in the fishing nets, they wouldn’t be able to surface.

On October 20, 2019, Fang Li on the ship with descendants of the POWs for a reunion.

Is it possible to recover the remains of the victims? I also investigated that. In the UK, I consulted Major Brian Finch of the Veterans’ Association, who is also a military advisor for this film. He introduced that ships sunk during wartime can be regarded as War Graves (military cemeteries) and should not be disturbed. We had some debate about this. I argued that the victims onboard the Lisbon Maru did not die in combat; instead, they were tortured to death as prisoners. The Lisbon Maru underwater should not be seen as a grave, but as a prison, where more than 200 British soldiers were nailed into the hold and unable to escape before it sank. In 2018, I conducted three surveys among the descendants of the captured British soldiers, and their opinions were roughly split; some wanted the remains of their relatives to be brought home, while others believed that, according to the tradition of War Graves, they shouldn’t be disturbed.

<