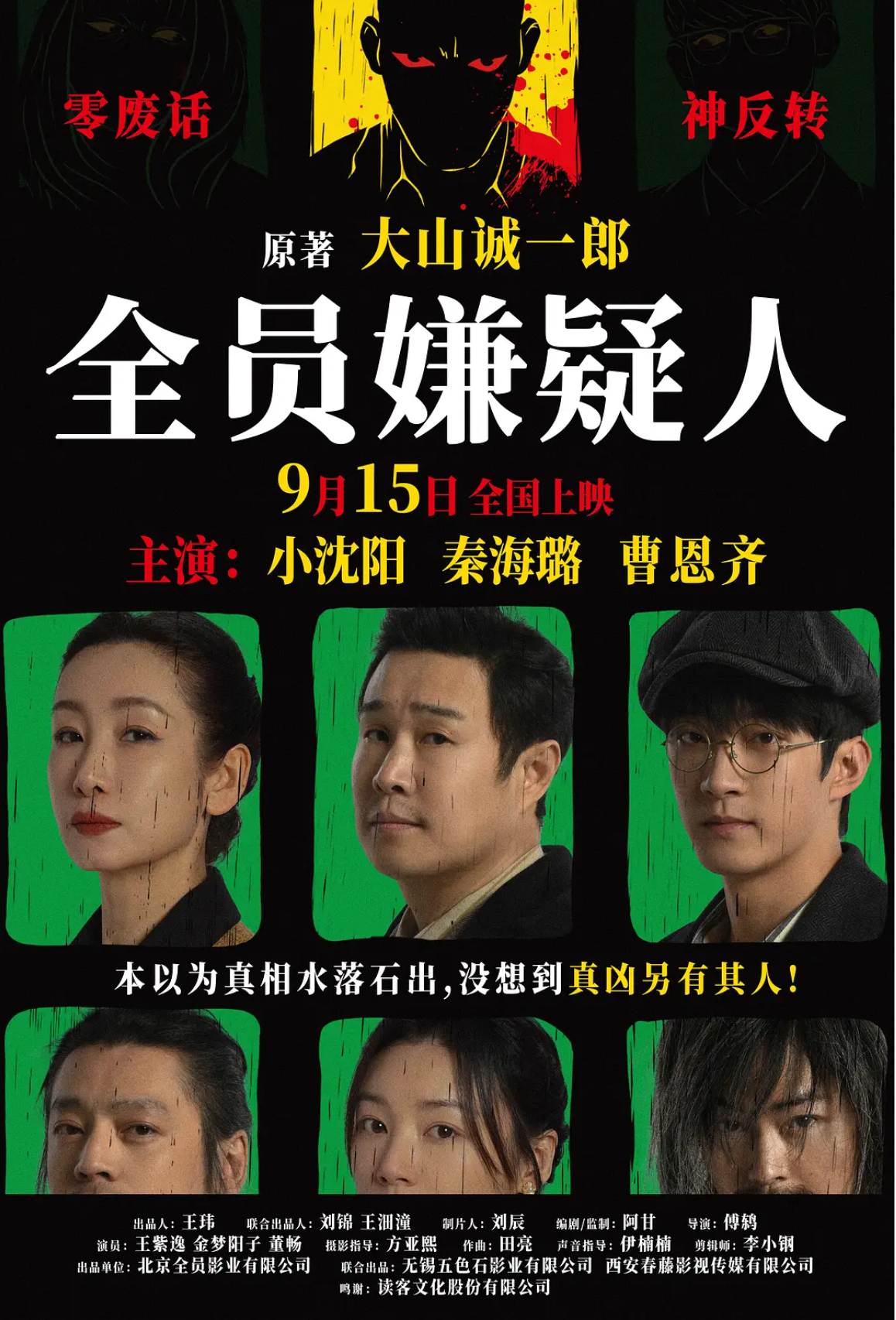

As a long-time fan of detective stories, "All Suspects" is a movie I’ve been closely following during the Mid-Autumn Festival release period, especially since it’s a rare domestic film adapted from a classic Japanese detective novel.

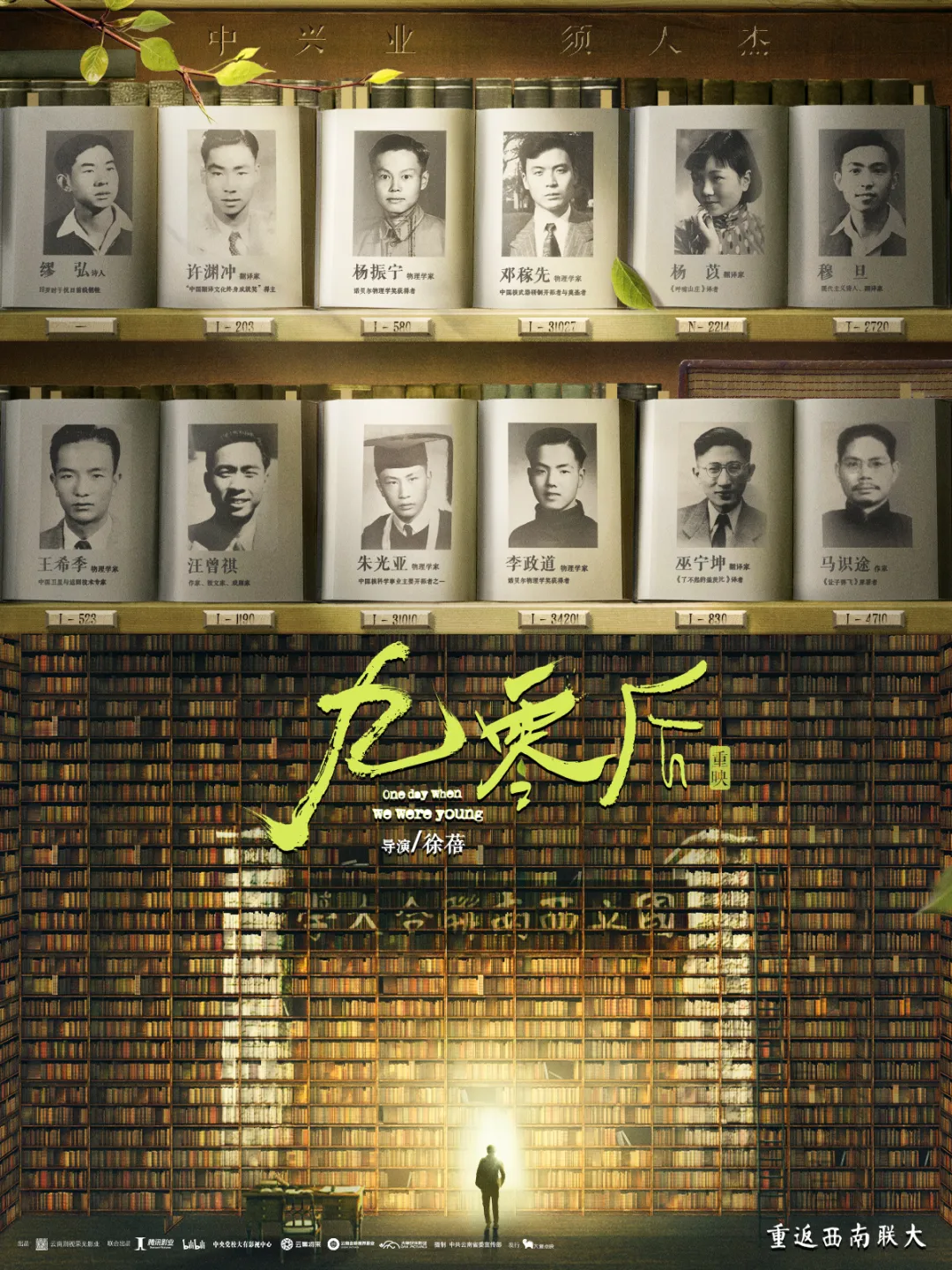

Poster for "All Suspects"

Previous Chinese films have adapted various Japanese mystery novels, but most have leaned towards social detective stories, such as Keigo Higashino's "The Devotion of suspect X" and "The Mirrored Blade," among others. Social detective stories typically use a case as a starting point to delve into real-world issues and discussions of human nature, with the crime method and the puzzle-solving process being of secondary importance.

In contrast, classic detective fiction focuses on the intricacies of the crime and the process of unraveling the mystery, pursuing clever plot designs and the enjoyment of untangling the truth. There are very few classic detective films in China, with recent notable examples including "Detective Chinatown" and "Big Name." If we narrow it down to adaptations of Japanese classic detective novels, I can’t think of any at all.

The original source material for this film is the short story collection "All Suspects" by Japanese author Seiichiro Ooyama. Ooyama has focused on crafting short classic detective stories, with several of his well-known works ("The Alphabet Puzzle," "Museum of Tricks," "The Collector of Locked Rooms") being published in China, making him a familiar figure in the domestic detective community.

Some of Seiichiro Ooyama's notable works and their Douban ratings

Ooyama's unique feature is his imaginative plot designs, often filled with ingenious ideas that elicit applause. However, one of the most criticized aspects of his work is his lack of focus on evidence; the reasoning often relies heavily on imagination to connect various clues, fabricating a seemingly flawless truth but lacking solid, reliable evidence. The conclusion usually involves pinpointing the culprit and then seeking evidence, or having the culprit confess after the deduction is presented.

In the collection "All Suspects," Ooyama uniquely positions the protagonist as a detective who lacks deductive abilities but possesses a special talent called "Watson Power," which amplifies the deductive capacities of those around him. Thus, every time a case arises, the suspects transform into Sherlock Holmes, identifying what they believe to be the murderer, while the accused must also refute their theories.

The quality of the stories in this collection varies, but the first story "The Crimson Cross" is considered the best. The challenge lies in the fact that it’s merely a short story; adapting it as it is would result in a runtime just over half an hour, so how would the movie stretch it to over 90 minutes? Let’s discuss the adaptation strategy of the film.

The film's main storyline largely follows the original where the protagonist detective checks into a guesthouse on vacation, which also includes the owner, a waitress, and three other guests. Early the next morning, they discover that the owner and the waitress have been shot, with five blood-red crosses drawn on the floor of the owner’s room. Under the influence of Watson Power, the three guests embark on a competition to deduce the murderer.

Still from "All Suspects"

The film relocates the setting from modern Japan to 1937 China, with Xiao Shenyang portraying the protagonist who still possesses Watson Power, while the identities of the other three guests are changed to fit the setting: a drifter, a female writer, and a pianist. The movie also localizes other aspects, such as providing explanations for the bloodied crosses that are more relatable to Chinese audiences compared to the original Japanese contexts.

To fill out the content, many roles were given additional screen time. The story involves a bank robbery case from five years ago; in the original work, only the murderer was related to the robbery, while the film broadens the character relations, linking all three guests to the robbery and adding a love triangle between the victim and the murderer (the original only featured a monetary dispute), further heightening the drama of the story.

The film’s major modification from the original occurs at the ending. After identifying the original murderer, the film introduces a new twist, revealing the existence of another killer, akin to what the poster claims: just when you think the truth has come to light, the real culprit is someone else.

In terms of structural skeleton, the adaptation strategy is not flawed, but when it comes to specific plot details, it’s riddled with holes that make it hard to overlook.

First, regarding the film's style, the production team seems to have attempted to utilize Xiao Shenyang’s comedic persona by giving his character a substantial amount of humorous scenes. The issue is, however, that this is not a comedy, and the other characters lack comedic moments, resulting in a film where only Xiao Shenyang delivers awkward jokes that aren’t picked up by anyone else, creating a dissonance in the film’s tone that feels out of place, making the overall style feel fractured.

Still from "All Suspects"

Next, addressing the core deduction process, there are numerous logical issues here that make it completely insufficient as a classic detective story.

Firstly, there's the issue with the protagonist’s setup. Like in the original, the film starts by emphasizing that the protagonist has little deductive ability, solving cases entirely by harnessing Watson Power to enhance the deductive skills of those around him. However, the production team seems to have felt that the protagonist needed more presence, so they had him become significantly involved in the deduction process in the latter part of the movie, which ultimately allowed him to uncover a major portion of the truth, thereby nullifying the significance of the Watson Power concept.

The protagonist’s involvement in the deduction brings about an even more critical issue: it undermines the original competitive deduction process among the three guests. In the original, the deduction flow involves A accusing B, B accusing C, C accusing A, and then A accusing B again. Throughout this mutual accusation and rebuttal process, the three constantly eliminate incorrect answers and uncover new clues, ultimately identifying the murderer. This deduction process is tightly interconnected and very rigorous.

But in the film, because the protagonist also participates in the deduction, and the production team hasn’t added new content to the original reasoning procedure, they simply shift the other characters' deductions onto the main character. This leads to an awkward situation where three characters simultaneously declare, "I know who the murderer is," yet only two provide their reasoning, and after they finish deducing, the protagonist starts his deduction, leaving the third character seemingly forgetting their own proclamation and never explaining their understanding of the clues by the end of the film.

Still from "All Suspects"

It would have been better to simply eliminate the Watson Power setup entirely, which would have avoided the forced situation of having three people declare simultaneously that they know who the murderer is, and would not have left such a significant plot hole.

With regard to the core deduction process, the film adaptation introduces a series of logical issues. The key breakthrough in the original work is realizing that the owner’s room is not the crime scene; after being shot in the killer’s room, the owner does not die immediately but instead escapes back to his own room to evade the killer, all framed in simple and clear reasoning.

However, the film designs the scene where the killer shoots the owner as an accidental murder, with the killer panicking and not intending to pursue the owner. After being shot, the owner smiles, revealing an expression of relief before dragging himself back to his room. Why would the owner show such an expression? Does he appear to have accepted his death? Why would he persist in walking back to his room? The film fails to clarify this, relying entirely on audience assumptions.

The film’s adaptation also disrupts the logic used to identify the culprit. In the original, the guesthouse’s layout is somewhat unique; only from certain rooms can one access the owner’s room, and together with other clues, one can use the process of elimination to uncover the culprit. However, the film alters the guesthouse to resemble a traditional courtyard, allowing access to the owner’s room from other rooms, thus making it impossible to establish who the murderer is.

Still from "All Suspects"

To overcome this problem, the film resorts to a very blunt solution, which I won’t spoil, but to give an analogy: someone finds a sock left behind by the murderer at the crime scene; whoever wears the same pair of socks is the murderer, and upon seeing the irrefutable evidence, the murderer confesses.

I previously mentioned that the main appeal of classic detective fiction lies in the enjoyment of meticulously unraveling the truth, but viewers cannot experience this in the movie; instead, they likely feel that the screenwriters have been overly lazy, abruptly inserting such a crude and unprepared new clue at the end—an absolute taboo in classic detective writing.

Furthermore, the film’s murderer is just too easy to guess; the character has been given too many scenes suggesting their guilt. Generally, such characters serve as smokescreens to mislead viewers, often leading to further twists, but in this case, the murderer turned out to be the one with the most evident guilt (the twist at the end does not upend the murderer’s identity), which is probably the biggest surprise the film offered me.

Overall, this film is a comprehensive degradation of the original work, particularly its core deductive elements which are filled with flaws and unable to withstand scrutiny. I’d recommend that those interested go check out the original instead.