Note: This article contains serious spoilers

Note: This article contains serious spoilers

Note: This article contains serious spoilers

Some viewers have remarked that watching The Old Gun reminds them of Steel Piano, and I share that sentiment. This is not only because both films feature Qin Hailu— even if Gu Xuebing (played by Zhu Feng) survives the gunfight, the likelihood of him ending up with Jin Yujia (also played by Qin Hailu) seems slim. More often than not, life does not go as intended, resulting in forced separation, and one can imagine him contemplating building a "steel piano" for Geng Xiaojun (played by Zhou Zhengjie).

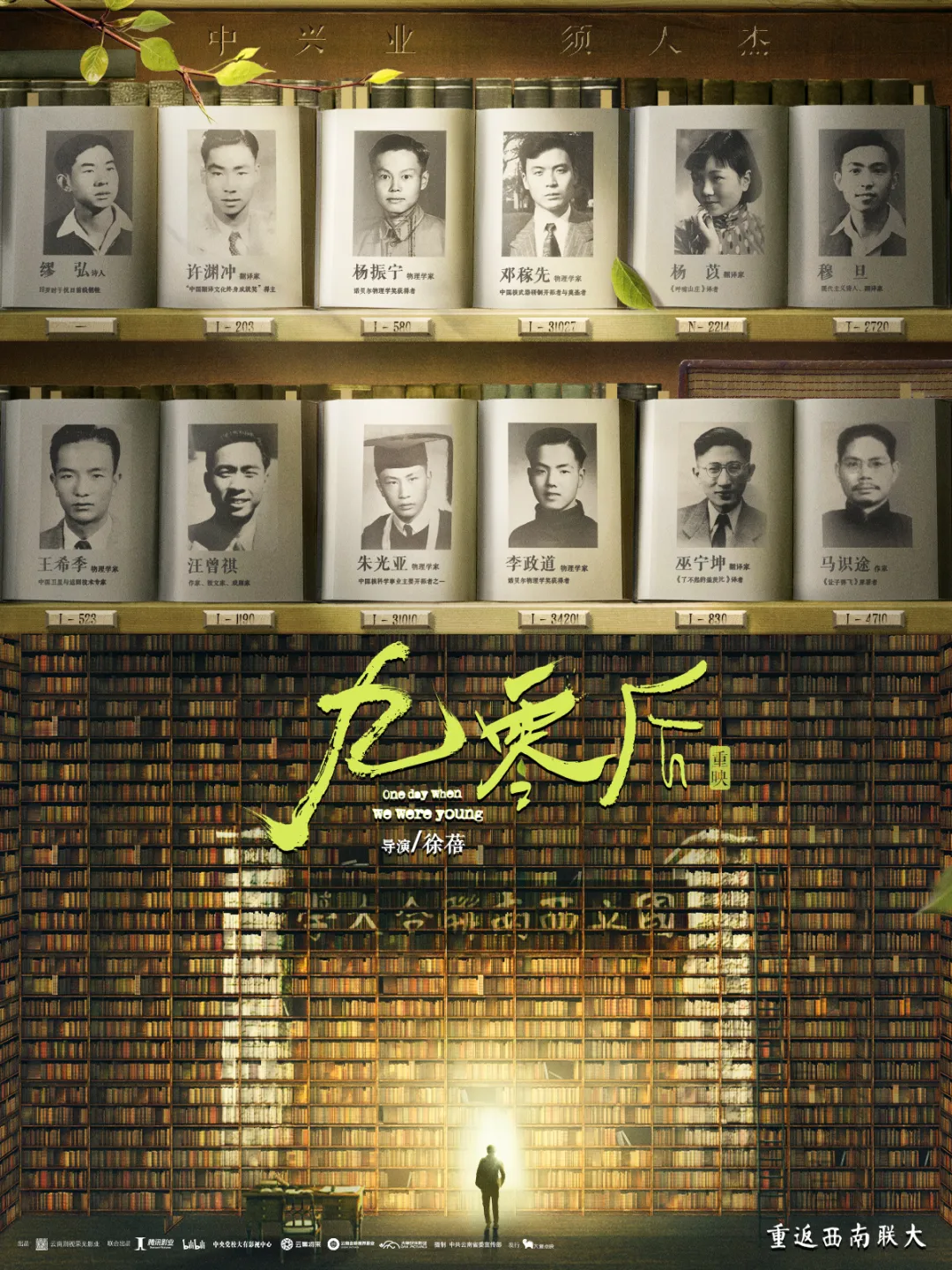

Poster of The Old Gun

This is probably the fatal dilemma that The Old Gun faces. It's not that the artistic quality of the film is lacking, nor can we say that the creative team did not put in their effort, or that the film fails to probe history and society with sufficient depth; however, every path this film traverses seems to have been explored by others before.

Once again set in a factory in Northeast China, the film addresses the impact of ordinary people’s lives, the massive changes of eras, and the challenges they impose on life principles. In a way, Gu Xuebing can be seen as another Wang Xiang from A Long Season. They are both "stubborn," clinging to their notions of goodness and justice, which seem out of place in their environments. They both hope to improve the lives of those around them through their efforts, yet often end up making things worse due to their clumsiness.

This theme of scars in Northeast literature is well-established—when creators reflect on that history, it is not just to rehash old stories but to seek self-understanding through past times. This is why works from authors like Shuang Xuetao, Ban Yu, and Zheng Zhi always start from the perspective of the "younger generation," finding life’s strength in the fading figures of their parents.

Still from The Old Gun

This time, The Old Gun straightforwardly places the "younger generation" alongside their parents. The character dynamics between Gu Xuebing and Geng Xiaojun are likely to resonate with loyal readers of Northeast scar literature— the endurance and kindness of their parents attract the youth, while the energy and passion of the younger characters rekindle ideals and vigor in the older generation. The journey from conflict to mutual understanding and support is a process of reconciling with the past and history, which is the conventional pattern for such works.

As for the last shot fired by Gu Xuebing at the film's conclusion, it is not surprising. In Ban Yu's novel Pan Jin Leopard, the father, who has been portrayed as a coward, finally "lifts his head, stretches his neck, and shouts at the dust and nothingness, and everything suspended in mid-air, that voice foreign and mournful, like a letter, reaching distant places…" At that moment, the son "can no longer see his father's face."

This is nearly a prerequisite for all Northeast scar literature: providing an outlet for readers’ emotional release through dramatic conflict, while highlighting the protagonist's dignity and strength of character. In the cinema, I heard an audience member behind me quietly exclaim, "So accurate?" This is of course just a metaphor on an artistic level — Gu Xuebing may be a minor figure amidst the tides of the times, yet his commitment to justice can still strike the softest chords in people's hearts.

Still from The Old Gun

When we apply the usual analytical framework to this film, it all holds true. Therefore, we might summarize: while the film possesses the strengths of Northeast scar literature, it equally lacks the breakthroughs and innovations that audiences yearn for.

I'm not sure when it started happening, but people increasingly resort to grand terms to describe or embellish Northeast scar literature. It is "the era" that has destroyed the protagonist or "the tide" that has marginalized them, but what exactly are "the era" and "the tide"? It is telling that few works can withstand such inquiries.

Take this film, for instance. Gu Xuebing's colleagues selling machinery and parts from the factory are driven by necessity, which is understandable; the factory manager turning a blind eye to subordinates selling public assets does so merely to pay thousands of workers; Tian Yonglie (played by Shao Bing) takes risks by resorting to robbery out of desperation; Geng Xiaojun's good brother sneaks into the factory to steal at night, triggered by family poverty…

How should one interpret this? Everyone has faulted, yet no one is entirely at fault, leading us, yet again, to attribute the protagonist's misfortunes to the abstract and monumental "tides of the times." If we must assign blame, perhaps the indecisive and cowardly small factory leaders in the film could bear some responsibility, but to lay the sins of the era at the feet of specific individuals seems inappropriate.

After the movie, there’s a small epilogue where Gu Xuebing and his brother Tian Yonglie, along with Geng Xiaojun and his good friends, share laughter and gradually fade into the overgrown backdrop. The intention here is unmistakable—this film is a dirge for countless "Gu Xuebings" who have vanished in the currents of time.

However, as previously mentioned, we have already experienced this poignant and melancholic tone in Northeast scar literature too many times. Readers and audiences still want to ask: what is truly going on here? Who will take responsibility for all of this?

Objectively speaking, we cannot reduce a novel or film to a scientifically rigorous sociological investigation, but when realistic narratives reach a standstill, relying on romanticism as a camouflage seems to have become a common creative routine.

In recent years, "Northeast" has become a buzzword in the visual world. Be it mystery-solving or love stories, an increasing number of works are re-stereotyping this land. A typical example might be Jin Yujia— in Northeast scar literature, women from the Northeast are often portrayed as loud and seemingly tough, yet their spiritual essence remains enduring, gentle, kind, and accommodating. They resemble an "ideal mother" imagined by the author but unknowingly turn into mere backdrops for the protagonists. Rather than indicating insufficient skill from the creator, it suggests that formulaic creative approaches are limiting many authors' imaginations.

In this sense, the film might have been better off allowing Gu Xuebing's most ideal shot to remain in his imagination and pursue realism to the end. Since the work aims to depict a person subdued and repressed in a grand era, it should not serve us a bowl of soul-soothing clichés — how could a middle-aged man, who has long neglected his talents due to years of insufficient training, possibly redeem his life with a single shot? Colleagues who turn to crime cannot meet favorable ends, and even Gu Xuebing's unwavering commitment to justice ultimately proves futile. This is a harsh conclusion, but it is the essence of real life, isn’t it?

This again reminds me of Zheng Zhi's novel Xian Zheng, which became unexpectedly "warm" and "healing" after being adapted into the film The Hedgehog. To me, this exemplifies the true tragedy of Northeast scar literature.