The film "Good Things," directed by 90s-born director Shao Yihui, is his second feature film. As a “parallel piece” to his previous work “Love Myth,” it features dense dialogue and is rich in insightful humor, maintaining the director's deep observations of gender relations and various social issues, as well as his exquisite and delicate visual style.

What sets it apart is that the Shanghai dialect version of “Love Myth” blends a sense of melancholy and acceptance with a hint of innocence that comes with age, like a dream just before awakening after a long sun-soaked slumber. In contrast, the Mandarin version of "Good Things" is broader, more complex, and full of vitality, as refreshing and bright as dancing barefoot on the grass.

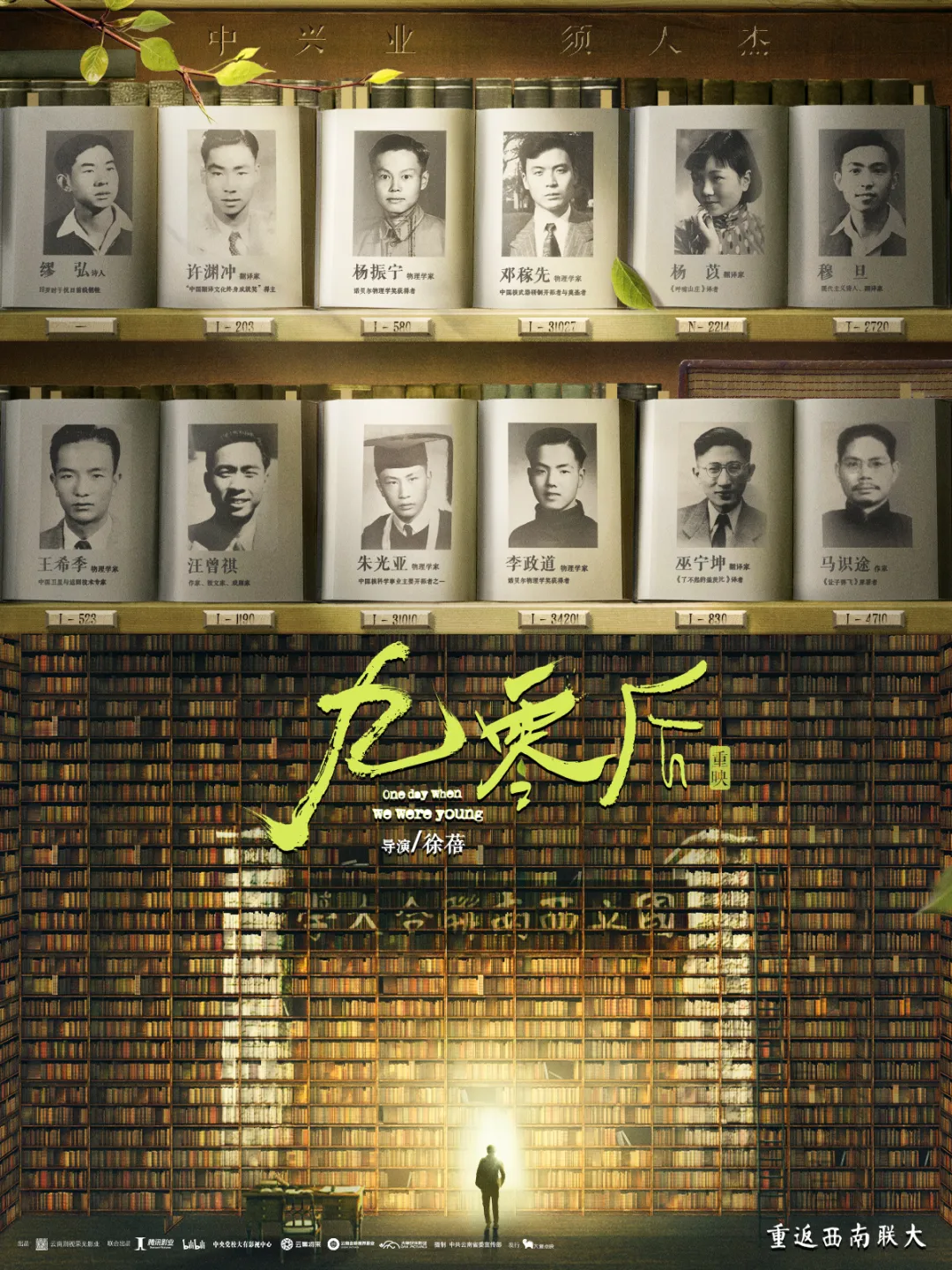

Poster of "Good Things"

The story unfolds in Shanghai, featuring 25 iconic landmarks and involving 51 smaller scenes within the city. Here, “Shanghai” highlights a modern, open, fashionable, and diverse lifestyle. What can be labeled as "Good Things"? Borrowing the words of the film's protagonist, Wang Tiemai, it’s "things that make you happy," and while "happiness" seems simple, it is indeed rare—thankfully, "Good Things" is genuinely a "good thing."

Poster of "Good Things"

Describing "Good Things" merely as “relaxed,” which is favored by today’s youth, doesn’t capture its essence. What makes it truly “good” lies in the film's light quality. Relaxation serves as a heavy contrast, merely intermittent breathing amidst overburdening, while lightness lifts effortlessly, like a wing gliding over water, deeply resonating with the incomprehensible weight of life, fostering a profound understanding that allows one to transcend existing cognitive frameworks and rethink within a broader perspective.

This self-assured, calm, and transparent lightness manifests in the film as a childlike sincerity, devoid of binary judgments regarding superiority, beauty, or competition, free from anxieties stemming from such dichotomies. It is merely the ordinary—reflected in human interactions—unshackled by certain inherited ideas.

Of course, this return to authenticity is not devoid of ideal filters; it results from meticulously crafted effects across the film's scenes, performances, colors, music, and tonal imagery, even bearing the drawbacks of some characters appearing as mere plot devices. Yet, just as Wang Tiemai characterizes a complex emotional relationship as “a ten-minute break” in her life, isn’t "Good Things" also a momentary respite for weary urban souls? It builds a warm narrative that allows anyone to become a child, bravely confronting their inner selves while nurturing the possibility for change in their present and future.

Still from "Good Things"

Unlike commercial genre films, "Good Things" lacks intense dramatic conflict or a clear storyline, yet it gradually enhances the audience's sense of immersion without them realizing it. The film narrates the story of single mother Wang Tiemai, her neighbor Xiao Ye, and daughter Wang Moli, who, facing their respective hardships, rely on and warm each other, ultimately gaining clarity in reality and strengthening their selves. The narrative flows subtly between lines, dense dialogues, and a plethora of “straightforward” statements, combined with humor born from vast contrasts between expectation and reality, all complemented by appropriately-layered emotional music, creating a friendly and tolerant narrative atmosphere. The viewing experience feels like chatting casually with a friend over slow music, sipping coffee, where nothing is unspeakable amid understanding companionship.

Consequently, a unique aspect of "Good Things" lies in its narrative drive, which does not stem from characters filled with dramatic tension or intricate relationships but from the characters’ very states. For instance, Wang Tiemai’s independence, Xiao Ye’s commitment to love, and Wang Moli’s refusal to follow suit. These character states continuously evolve, eluding a categorical label or simple reduction to behaviors or emotional entanglements; they resemble floating islands with distinct landscapes within the storytelling.

The film opts out of the linear narrative commonly found in narrative films or the non-linear storytelling seen in art films that disrupt temporal and spatial relationships. Instead, it features a seemingly fragmented narrative, akin to snippets from a stand-up comedy routine, yet it is cohesively integrated through the radiance emitted by the three characters and their interactions.

Still from "Good Things"

The three main female characters represent crucial life stages of women from childhood to youth and middle age, each facing contradictions arising from self-identity, social relationships, and gender roles. From another perspective, these roles, while sharing commonality across their life journeys, carry distinct spiritual dimensions, thereby constructing a rich understanding of women in their societal context, presenting a multifaceted “present continuous” feminist viewpoint.

Wang Tiemai, representing middle-aged women, seeks to compete fairly with men under patriarchal logic through self-motivation, embodying an all-rounder who never succumbs to defeat despite encountering repeated setbacks. Xiao Ye, representing young women, confronts her emotional needs and her sensitivity, often quipping, “Men can be quite fun,” approaching male relationships without a definitive rupture, transitioning from deliberately pleasing to conscious choices that prioritize freedom in personal life and autonomy. Nine-year-old Wang Moli symbolizes a burgeoning generation of women, who remain sensitive to the subtle injustices obscured by power and reject internalized conflicts, poised to innovate rules.

Still from "Good Things"

The primary female characters and the ensemble of women, including Wang Moli's homeroom teacher and Wang Tiemai's colleagues, endeavor to fulfill the post-feminist pursuit of personal autonomy and diversity. For instance, Tiemai and Xiao Ye’s handling of gender relations subtly aligns with post-feminist frameworks centered on female consent, equality, participation, and pleasure. On the other hand, the complexity and polysemy expressed by women in the film resonate with Raymond Williams’ assessment of societal culture—as a blend of past, present, and future or conservative, mainstream, and avant-garde cultural elements that are perpetually evolving rather than static or singular.

The interactions of the three women in "Good Things," akin to those undergoing transformation, do not overtly display antagonism toward certain ideologies; they are molded by entrenched concepts while awakening and evolving, experiencing shifts in perspectives that once seemed unshakeable.

Still from "Good Things"

Wang Tiemai, Wang Moli, and Xiao Ye forge a new, tiny alliance. Unlike familial bonds found in Hiroshi Ishikawa’s films like “Shoplifters” and “Broker,” the female community in "Good Things" is more emotionally attuned, exuding warmth, lightness, and tenderness. Their names (Mei, Moli, Yezi) represent sunward plants—resilient, beautiful, and non-aggressive. During multiple encounters with real-life challenges and emotional crises, they consistently play roles of mother and daughter or friends, supporting and comforting each other. This bond is not based on economic or ethical common interests but rather reflects friendships deeply resonant with women’s psychological and emotional needs.

Still from "Good Things"

The film entirely escapes the male gaze commonly found on big screens in the past and presents a praiseworthy audio-visual montage for this year’s Chinese cinema. The dolphins diving, pandas munching bamboo, deserts, and tornadoes perceived by Wang Moli symbolize the profound and subtle sounds of nature; in reality, they're reminiscent of her mother Tiemai's everyday sounds of washing vegetables, cooking meals, cleaning houses—ordinary routines. This juxtaposition of grandeur and the mundane, the distant and the immediate, the spectacular and the everyday can be interpreted as a recognition and appreciation of women’s often undervalued labor in domestic spaces, signifying that even while confined within tight family circles, a woman's spirit can still soar vast expanses.

This juxtaposition's clearest social significance may be raising the voice for women trapped within domesticity. The film's English title “Her Story” can be seen as both a narrative focused on her experiences and as a critical theoretical spotlight in feminist studies—the "herstory" referenced alongside history, symbolizing women's writing, history, and perspectives. Additionally, the film intricately embeds unspoken internal dialogues, such as phrases seen on clothing and bags, as well as that metaphorical elephant in Xiao Ye’s room, which represents societal blindness toward significant issues.

Still from "Good Things"

Undoubtedly, "Good Things" embodies a distinct consciousness of femininity and female expression. Incorporating Wang Moli's double entendre, “I don’t want to box,” the film's theme extends beyond this. In fact, it presents a narrative rich with varied themes—women’s growth, emotional experiences, family, relationships, and socio-political commentaries surrounding original family influences, class division, regional differences, media ecology, educational philosophies, bureaucratic structures, as well as issues pertaining to authority and online violence.

The male characters within the film—be it Wang Tiemai's ex-husband, drummer Xiao Ma, Dr. Hu, or Wang Moli’s classmate Zhang Jiaxin—are less multifaceted than their female counterparts, often caricatured as representatives of specific male archetypes, yet they also inhabit their own dilemmas. Commonly, such predicaments arise from being identified as men, compelled to adhere to the external/internal dichotomy of gender roles, striving for exceptionalism, and facing societal pressures where a man's ultimate vanity can be witnessing a woman risking everything for love, even to the point of death. In some respects, men share a binary logic with women within a singularly successful framework or power structure, bearing the pains of the other side of the coin.

Still from "Good Things"

Thus, "Good Things" doesn’t seek to belittle or denigrate men or create gender antagonism; rather, it presents certain issues with a gentle touch, depicting them plainly and honestly (for instance, menstruation doesn’t need to be ashamed of; remain vigilant against feminism becoming a politically correct narrative or capital symbol; and acknowledging that men, too, need emotional healing). It firmly says no to the prevailing dual rules—a sentiment shared by Wang Tiemai and Xiao Ye towards themselves and particularly their expectations of Wang Moli.

Wang Moli is repeatedly referred to as a "child" within the film, akin to the child in "The Emperor's New Clothes," unabashedly expressing truths obscured by adult pretenses in the adult world. "Child" here stands for a state, an attitude, and in many ways embodies the future. The film addresses life issues candidly, devoid of sentimentality, preachiness, irony, or glorified undertones, infused with genuine hope that every individual can reassess the various constraints posed by society and self, granting themselves permission to fail, to relax, to feel confusion, and to resist conformity... in a surreal space where the material world and the spiritual realm coexist, allowing daily life’s divine radiance to shine, embracing the essence of being a child.