On the edge of the Giza Plateau outside Cairo, just 2 kilometers from the pyramid complex, a landmark building—the Grand Egyptian Museum—finally opened to the public on November 4, 2025, after 20 years of construction.

This archaeological museum, the world's largest single-civilization archaeological museum built at a cost of over $1.1 billion, not only houses more than 100,000 ancient Egyptian artifacts, including the first complete and comprehensive display of over 5,000 funerary objects from Pharaoh Tutankhamun, as well as artifacts such as the Great Solar Boat of Khufu and the Colossus of Ramses II, but it is also a gem of architectural art. Surprisingly, the museum's design, described as "representing the fourth pyramid of Egypt," was actually the work of Chinese-American architect Shih-Fu Peng and his Irish firm, Heneghan Peng Architects.

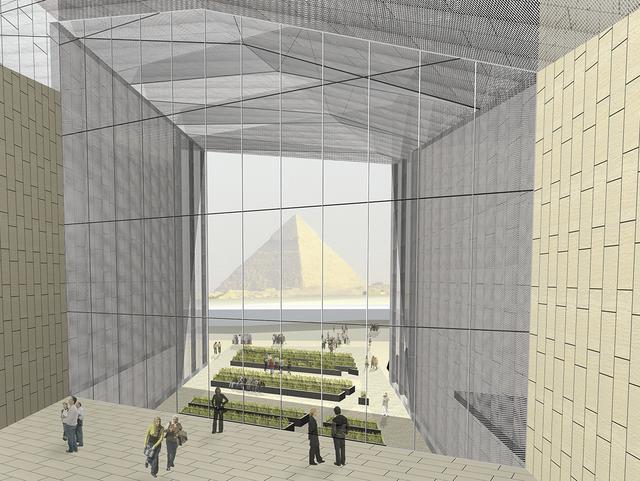

Museum interior

A design competition from over 20 years ago: A dialogue spanning a millennium.

In 2002, the Egyptian government launched a global design competition to build a brand-new museum, attracting 1,557 architectural teams from 83 countries, making it the second largest architectural competition in history. In 2003, Heneghan Peng Architects was announced as the winner. The firm was founded in New York in 1999 by Taiwanese-American architect Shih-Fo Peng and his Irish wife, Róisín Heneghan, who later settled in Dublin, Ireland. Shih-Fo Peng's father, Yin-Hsuan Peng, was a renowned early architect in Taiwan.

Róisín Heneghan (left) and Peng Shifu (right)

Facing the world-famous pyramids not far away, any new building would likely pale in comparison. But Peng Shifu's solution lies in the "middle way"—neither too much nor too little. He cleverly placed the museum between the plateau and the plain, neither competing with the pyramids on the plateau nor completely disappearing from the plain.

The museum features a radial, cliff-like structure, with the roof height gradually decreasing towards the pyramid, creating a sense of depth. This design allows the museum to complement the pyramid, creating a harmonious resonance.

The location of the Grand Egyptian Museum and the pyramids

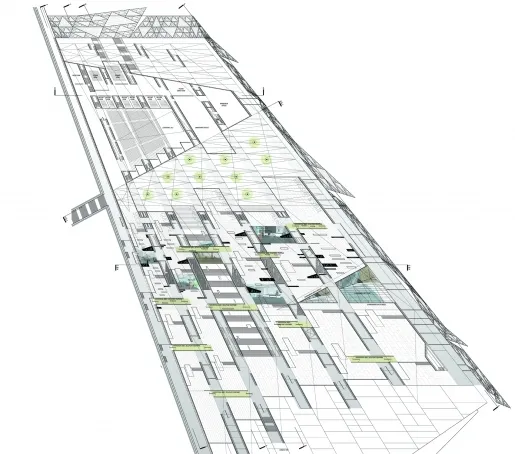

Museum site design and Giza pyramid complex schematic diagram

The building's layout was meticulously calculated, with its axis precisely aligned with the Great Pyramid of Giza and the Pyramid of Menkaure. A visual axis runs through the museum, ensuring the pyramids remain a constant backdrop during the visit. The museum cleverly utilizes the nearly 50-meter elevation difference between the edge of the Grand Canyon and the Nile Valley. The building's volume appears to grow out of the site, cascading towards the pyramids in layers, ultimately blending into the desert plateau. This "moderation" allows the building to neither overshadow the site nor lack a noticeable presence.

Grand Egyptian Museum

Museum visitors

Architect Peng Shifu incorporated the Chinese cultural principle of "the golden mean" into the design, achieving a balanced relationship between the architecture and the ancient site. The design also drew inspiration from the ancient Egyptian view of life and death—the Nile Valley to the east representing life, and the desert pyramids to the west symbolizing death; the museum itself became a medium connecting life and death. Ancient Egyptians believed that sunrise symbolized "life," and sunset represented "death." The Grand Egyptian Museum, situated between the arid plateau (the pyramids) representing death and the fertile Nile Valley plain representing life, became a bridge connecting life and death.

The museum's inverted triangular shape, like a giant arrow, tightly connects the Giza Plateau and the Nile alluvial plain. The ancient Egyptians called the high-altitude desert region "red land" and the alluvial plain "black land," and the unity of these two lands represented the unity of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Architectural features: Visual resonance with the pyramids

The Grand Egyptian Museum's architectural design is ingenious, forming a close visual connection with the surrounding environment, especially the pyramid complex.

In the competition design for the Grand Egyptian Museum, the museum's (right) volume was pushed downwards as much as possible to ensure that the view of the pyramids would not be obstructed.

The museum's three axes radiate outwards to the three pyramids, embodying a sense of an epic, timeless history. The north and south walls of the building are precisely aligned with the Great Pyramid of Giza and the Pyramid of Menkaure.

Design proposal for the Grand Egyptian Museum by Heneghan Peng Architects

Most remarkably, the highest point of the museum's roof rim points to the summit of the Great Pyramid of Giza, the largest of the pyramids, while the other points point to the summits of the two smaller pyramids.

Upon entering the museum, the visitor experience is designed as a ritualistic journey. A magnificent six-story staircase is the climax of the sequence, flanked by statues of 87 ancient Egyptian kings and gods, guiding visitors upwards.

Museum rendering

View of the pyramids from inside the Grand Egyptian Museum

When visitors reach the top of the steps and are awestruck by the pyramid complex, the dialogue between ancient and modern civilizations reaches its climax.

The museum's interior design is also ingenious. In the center of the hall stands a colossal statue of Ramses II, which is 3,200 years old, welcoming every visitor with its magnificent presence.

Interior of the Grand Egyptian Museum

exterior of the Grand Egyptian Museum

The choice of building materials for the Grand Egyptian Museum reflects a fusion of tradition and modernity. The most striking feature of the building is its massive, translucent stone facade.

These stones form unique geometric patterns, allowing light to pass through during the day and emitting light from within at night.

The museum's roof is constructed of transparent metal, serving both energy-saving and sun-shading purposes. At night, the light absorbed by the exterior walls illuminates the interior, and visitors can see the three pyramids outside the museum from anywhere within the museum.

Interior of the Grand Egyptian Museum

Chinese-American architect Peng Shih-Fo: Let architecture and site engage in dialogue

Shih-Fu Peng, a distinguished Chinese-American architect, co-founded Heneghan Peng Architects with his Irish wife, Róisín Heneghan. Their work is renowned for its profound respect for and skillful integration with the environment, particularly its ability to create dialogue between architecture and site through an "anti-iconic" design philosophy.

Peng Shifu graduated from the Department of Architecture at Cornell University, while his wife, Róisín Heneghan, graduated from Harvard University. This academic background laid a solid foundation for their future careers. After graduation, they worked at renowned American architectural firms SOM and Michael Graves, respectively. This experience at large architectural firms allowed them to accumulate invaluable project experience. However, they were not content with this and yearned for more exploration and expression in architectural design. Before officially establishing their own firm, they used their spare time to participate enthusiastically in various design competitions to hone their design thinking.

In 1999, Peng Shifu and Róisín Heneghan officially established Heneghan Peng Architects in New York. Through frequent participation in international competitions in their early years, they gradually developed their own unique competition philosophy. They realized that the key to winning competitions was not piling up details, but rather presenting a very clear and powerful core concept that could immediately impress the judges.

Peng Shifu once summarized their experience this way: "If you struggle with an idea, then you should give up on it; if you can't describe your project in five or six words, then you can't win." This extreme pursuit of conceptual clarity became an important reason why they later stood out in many international competitions.

Peng Shifu

In 2003, Heneghan Peng Architects won the international design competition for the Grand Egyptian Museum, marking a milestone in their careers.

At the time, they were a small firm with only three members (including two founders and one student), yet they beat 1,557 competitors from 83 countries, making them a true "dark horse" in the architecture world. Following the Grand Egyptian Museum, Heneghan Peng Architects gradually grew and expanded. Their other works continue the core design philosophy of respecting the environment and integrating into the landscape, including well-known projects such as the Giant's Causeway Visitor Centre (2005-2012, Northern Ireland), the Palestine Museum (2016, Palestine), and the London Olympic Park Pedestrian Bridge.

Palestinian Museum rendering

Looking at Peng Shifu and his firm's work, one can clearly see some consistent design principles: anti-iconic architecture. They do not pursue ostentatious, self-centered architectural forms, but rather respond to the environment as humbly as possible. As Peng Shifu said, "My Chinese heritage taught me a certain humility, a respect for elders. To a large extent, all our buildings respect the environment."

Buildings in the Landscape: Unlike some architects who make buildings the main feature of the landscape, Heneghan Peng Architects prefers to let buildings grow out of the landscape and become part of the environment.

Peng Shih-Fo's architectural design resume showcases the journey of a Chinese-American architect who, through his profound cultural background, clear design thinking, and keen environmental insight, has achieved outstanding success on the world architectural stage. His works remind the world that architecture can be a humble yet powerful medium, skillfully connecting history with the present, and humanity with nature.

(Some information in this article is based on previous reports from Heneghan Peng's firm, The Paper, and Genius Factory.)