The name Lujiazui in Shanghai today comes from the former residence and ancestral tomb of Lu Shen (1477-1544), a scholar from the mid-Ming Dynasty, which is located here.

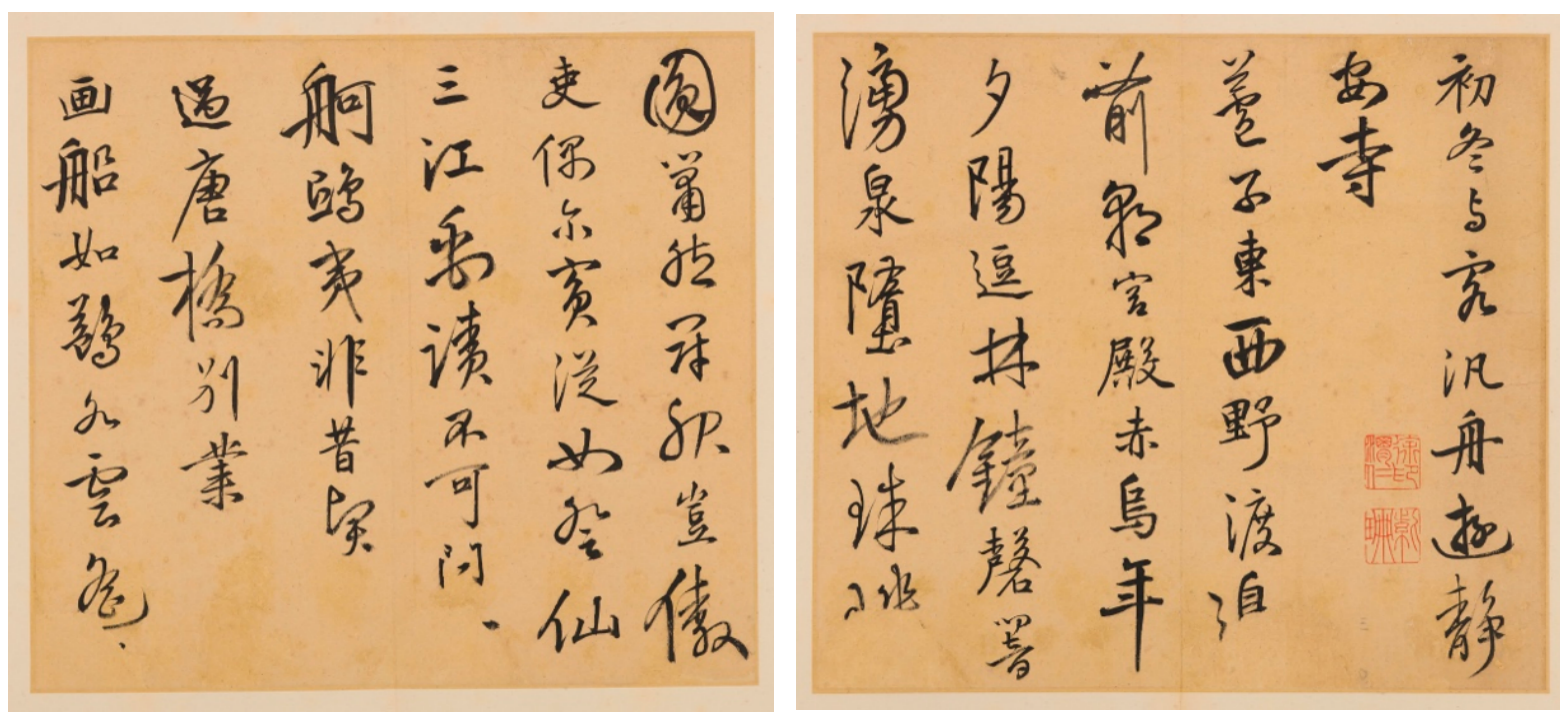

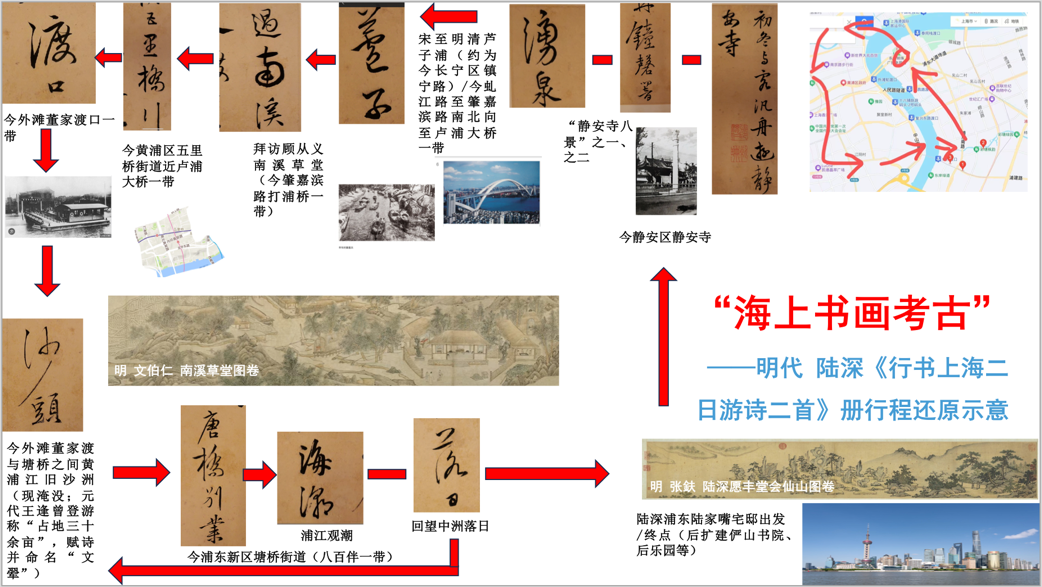

"Painted boats, like egrets, glide across the water and clouds, occasionally passing the Five-Mile Bridge over the South Creek." In late autumn and early winter, a chill lingers, and chrysanthemums bloom in the wind. Five hundred years ago in Shanghai, on an early winter afternoon, Lu Shen of the Ming Dynasty, on a trip to admire chrysanthemums and visit friends, left behind a masterpiece of calligraphy that has been passed down to this day—"Two Poems on a Two-Day Trip to Shanghai in Running Script," now housed in the Shanghai Museum. From the boat tour route described in the book, one can imagine the dense network of waterways in Shanghai at that time, with numerous canals, ponds, and streams crisscrossing to form the city's transportation arteries. The area covered by his two-day tour route roughly corresponds to the central urban area of Shanghai today.

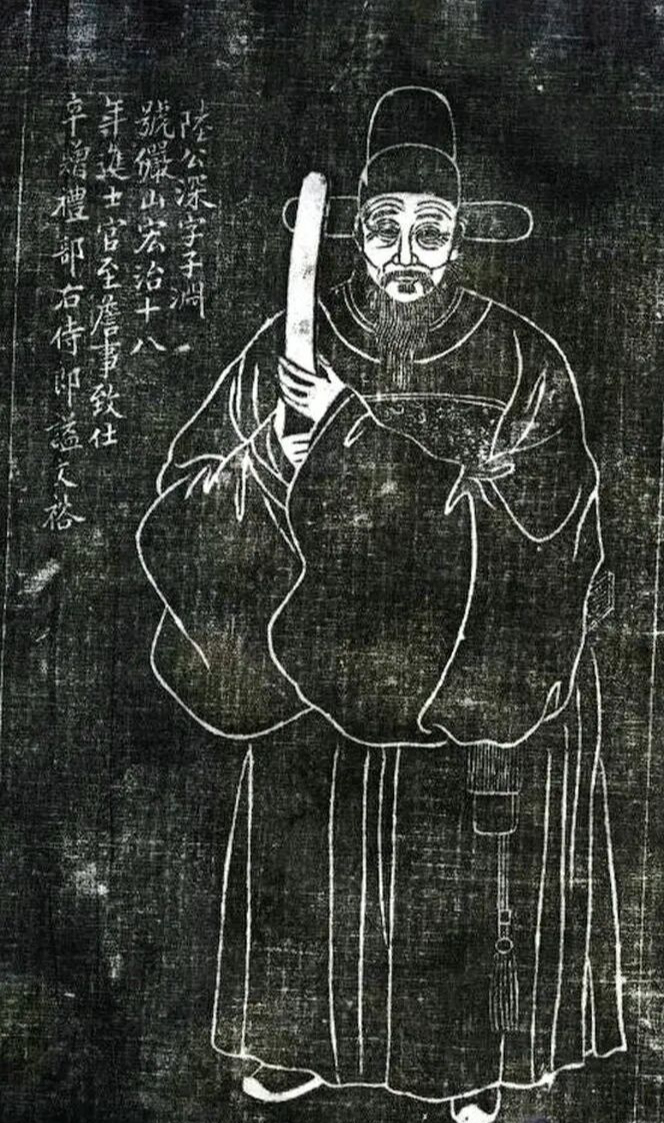

Lu Shen (1477-1544) was a scholar-official, calligrapher, historian, and writer in the mid-Ming Dynasty. His courtesy name was Ziyuan, and his pen name was Yanshan. He was from Shanghai County, Songjiang Prefecture. He passed the imperial examination in 1505 and was appointed as a compiler in the Hanlin Academy. He rose through the ranks to become the Grand Master of the Palace, retiring in 1541. His ancestral home was in Pudong, and the present-day Lujiazui area is named after his ancestral home and tomb. He was skilled in calligraphy, possessed a rich collection of paintings and calligraphy, was diligent in historical studies, and was proficient in poetry and prose. He was a prolific writer, with works including the *Yanshan Collection*. Lu Shen was the tenth-generation descendant of Lu Decheng, the younger brother of Huang Gongwang (whose grandfather and father lived in Lüxiang, Jinshan, Shanghai). Both were descendants of Lu Guimeng, a Tang Dynasty writer, and Lu Xun, a figure from the Eastern Wu Kingdom during the Three Kingdoms period.

Lu Shen's stone carving, see Songjiang Zuibaichi Bangyan's stone carving portrait.

In early winter, Lu Shen accompanied his guests from his home (the area around the Oriental Pearl Tower and Shanghai Center in Lujiazui, Pudong New Area) to board a boat from Shanghai Pu (the area around Waibaidu on the Huangpu River today), then through Xiahaipu (the area around Haimen Road in Hongkou District today) into the old Wusongjiang River (the area around Qiujiang Road in Jing'an District today) to travel west, then south through Luzipu (approximately the area around Zhenning Road in Changning District today) to visit Jing'an Temple. The two spent the night at Jing'an Temple. The next day, they continued south from Luzipu to Zhaojiabang and then east, passing "Wuliqiao" (near Lupu Bridge in Wuliqiao Street, Huangpu District) to visit a friend at Gu's "Nanxi Caotang" (in the area of Zhaojiabang Road and Dapuqiao). They then returned, crossing Huangpu (which connects to Shanghaipu to the north and was also called Shanghaipu at the time) from the ferry (which should be the area of Dongjiadu in the Bund). They passed Shazhou (i.e., Huangpu Zhongzhou) and arrived at Lu's "Tangqiao Villa" (in the area of Yaohan in Tangqiao Street, Pudong New Area) on the opposite bank to admire chrysanthemums. As the sun set, their friend returned home, and Lu Shen continued to board the boat and head north from Huangpu back to his Lujiazui residence.

Touring the scenic spots of his hometown and visiting friends to admire their calligraphy and paintings—these were two ordinary days in Lu Shen's secluded life. However, the long history and cultural heritage of the ancient temples in Jing'an reminded him of the ancient sages and worthies of this land. By the time Yu the Great tamed the three rivers, their landscape had changed; Fan Li had retired to the Five Lakes after achieving his goals. Did his own life of retirement and seclusion bear any resemblance to those of the ancients? On the second day, as he traveled home alone by boat, the setting sun over the treetops and the scene of fishermen and woodcutters in seclusion once again evoked his reflections on the past and present of reclusive life. The natural landscape had changed so much over time, yet the cultural heritage of this place continued uninterrupted. Two poems that had been brewing in his mind came to mind, and upon returning to his residence, he immediately picked up his brush and wrote them down. This is Lu Shen's "Two Poems on a Two-Day Trip to Shanghai in Running Script," now housed in the Shanghai Museum. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Two poems in running script by Lu Shen of the Ming Dynasty, depicting a two-day trip to Shanghai (collection of the Shanghai Museum).

These two poems were later edited by Lu Shen himself and included in his son Lu Ji's *Yanshan Collection*, with slightly altered titles: "Boating with Guests to Jing'an Temple on the First Day of the Tenth Month" and "Passing Tangqiao Village on the Second Day." Originally, these two poems, included in different versions of the collection, did not form a coherent narrative. However, based on the order of the poems on the artifact and the revised titles in the collection, we now know that the content is a continuous "Two-Day Trip to Shanghai." Only then can we, through Lu Shen's poetic imagery, return to a certain October 1st five hundred years ago and experience firsthand the Shanghai landscape as he saw it.

Figure 2 shows a reconstruction of the two-day tour itinerary from Lushen to Shanghai.

When the boat reached the ferry crossing on the east bank of Luzipu, the two disembarked. In early winter, the river was sparsely populated with boats, and the reeds on both banks were rustling in the breeze. Before them stood the solemn temple, its halls and pavilions majestic, and the sounds of bells and chimes echoing incessantly. This made him think of the grandeur of Jing'an Temple when it was first built during the Eastern Wu period, and he then composed a poem:

Boating with guests to visit Jing'an Temple in early winter

Lu Zi, east and west of the wild ferry crossing, the palace of the previous dynasty, the Red Crow year.

The setting sun teases the forest, the bells and chimes resound, and the gushing spring falls to the ground, its pearls round and pure.

His simple attire and elegant robes did not make him seem arrogant to officials; his occasional guests and attendants made him feel as if he were ascending to heaven.

The traces of Yu in the Three Rivers are no longer to be found, and the boat of Chi Yi is no longer that of the sages of the past.

Luzi Pu, also known as Xilu Pu, stretches from Zhaojiabang in the south to the Wusong River in the north. It was a major north-south transportation artery in western Shanghai County and one of the eighteen south-south tributaries of the Wusong River since the Northern Song Dynasty. These tributaries were collectively known as the "Eighteen Pu," including "Shanghai Pu," "Xiahai Pu," and "Lanni Pu." Luzi Pu begins at the intersection of present-day Zhaojiabang Road and Gao'an Road, flowing north through Huaihai Middle Road, Wukang Road, Huashan Road, Yan'an Middle Road, Nanjing West Road, Yuyuan Road, Wanhangdu Road, Kangding Road, Yuyao Road, Changshou Road, and Shahongbang, before crossing the Shanghai-Hangzhou Railway and flowing north into the old Wusong River (also known as Qiujiang). The names of present-day Luwan District (old administrative division) and the Lupu Bridge in Shanghai are related to this. Luzi Pu was the essential waterway for Lu Shen's journey south along the Wusong River. (Figure 2)

Figure 3 shows Luzipu in the 45th year of the Wanli reign of the Ming Dynasty (1617) on a historical map of Shanghai. Source: Shanghai Historical Atlas, edited by Zhou Zhenhe and produced by Shanghai Surveying and Mapping Institute, Shanghai People's Publishing House, 1999.

The "Three Rivers" refer to the "Dongjiang," "Songjiang," and "Loujiang," which were the three main waterways through which the ancient Taihu Lake flowed eastward into the sea. The ancient "Loujiang" is roughly equivalent to the present-day Liuhe River; the ancient "Dongjiang" has long been dammed; and the ancient "Songjiang" is approximately the present-day Wusong River, whose downstream section, the Suzhou Creek, eventually flows into the Huangpu River and then into the sea at Wusongkou. (Figure 3) The *Yu Gong* records that Yu the Great "dredged the Three Rivers and connected the Five Lakes." From the Song to the Ming dynasties, the landscape underwent tremendous changes.

Figure 4 shows the "Three Rivers" in the historical map of Shanghai. Map source: same as above, from the fifth year of Wu Yong'an (262).

As the sun sets and dapples the woods, the rosy clouds of sunset greet the approaching dawn. Lu Shen and his friends may spend the night at the temple. The following afternoon, they will board a boat at Luzi Ferry and set sail south from Luzipu. A painted boat, light as a bird, weaves through the water and clouds. Perhaps carrying a box of scrolls, they will pass Wuli Bridge and slowly reach Nanxi (meaning "south of Zhaojiabang"), visiting the Gu family's Nanxi Thatched Cottage. There, Lu Shen will have tea and a chat with his cousin, Gu Dingfang, whose sons, Gu Congli and Gu Congyi, may accompany them, admiring the calligraphy and paintings. After a short while, the two will board the boat to return, crossing the Huangpu River at the busy ferry crossing. They will see passengers coming and going, crowds of people, and as the boat passes a sandbar in the river, it will startle a flock of gulls and egrets. Amidst the rising and falling bird calls, the trees sway, and time flies by. The boat will dock, arriving at the Lu family's Tangqiao Villa in Pudong. On the second day of the tenth lunar month, when chrysanthemums were in full bloom, the two lingered at the thatched cottage to admire them. After bidding farewell to their guests, Lu Shen returned alone to his Lujiazui residence by following the tide, and recited a poem once more:

Passing Tangqiao Villa

The painted boats, like egrets, drifted across the water and clouds, occasionally passing the Five-Mile Bridge over the South Stream.

Pedestrians appear and disappear at the ferry crossing, while birds cry and sway on the sandy shore.

Together we admired the chrysanthemums at our thatched cottage, while I went alone to seek the source of the sea tide.

Countless lofty sentiments are entrusted to the river road, and the setting sun shines on the treetops where fishermen and woodcutters are seen.

The "sand dune" that Lu Shen saw while crossing the Huangpu River was likely "Huangpu Zhongzhou," which has a connection to Wang Feng (1319-1388). Wang moved to Wunijing (now Huajing Town, Xuhui District) in Shanghai at the end of the Yuan Dynasty and once visited the island with friends. At that time, Zhongzhou was already thirty acres in size, described as "a river flanking an island, like hills and mounds, truly a place where the water flows steadily," and named it "Wenhui." Zhongzhou is now submerged, and Ming and Qing dynasty records all state that it was located at the mouth of the Zhaojiabang River where it enters the Huangpu River.

The final couplet reveals Lu Shen's thoughts and feelings on this journey. He spent nearly forty years in officialdom during the mid-Ming Dynasty, and was favored by Li Dongyang (1447-1516). He passed the imperial examination in the same year as Yan Song (1480-1566), and his student Xia Yan (1482-1548) also became the Grand Secretary. However, his upright character and idealistic approach to life led him to stop his official career at the position of Grand Master of the Palace. But this did not hinder his reputation at the time. His collected works were prefaced by Fei Cai (1483-1548), Xu Jie (1503-1583), Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), Lu Shusheng (1509-1605), Xu Xianzhong (1469-1545), He Liangjun (1506-1573), and others, which shows his prestige among scholars and his important role in connecting the past and the future among the literati of Songjiang.

The Huangpu River in front of his home was a route Lu Shen always took, carrying with it many deep feelings and profound philosophical thoughts. Upon returning home, Lu Shen picked up his brush and wrote these two poems, signing them "Shen's draft, respectfully addressed to Shi Wang, a member of the literary circle." This indicates they were drafts for a friend. The recipient, "Shi Wang," is Yao Yun, courtesy name Shi Wang, author of *Zhu Zhai Ji*, a close friend of Lu Shen and also the teacher of his son, Lu Ji. Shortly before his death, Lu Shen even instructed in a letter home that "the epitaph should be given to Yao Shi Wang," demonstrating the depth of their friendship. Whether Yao Shi Wang also participated in this two-day trip is unknown. Lu Shen, Yao Shi Wang, and Gu Dingfang maintained close relationships, often involving calligraphy, painting, poetry, and literature.

Gu Dingfang (1490-1555), the owner of the Nanxi Thatched Cottage visited by Lu Shen on this trip, was Lu Shen's cousin, a descendant of Gu Jingyang (of the Tinglin school), and the 32nd generation descendant of Gu Yewang. His courtesy name was Shi'an, and his sobriquet was Dongchuan. A student of the Imperial Academy during the Jiajing era, he was skilled in medicine and was summoned to serve as a physician in the Shengji Hall. His family possessed a rich collection of calligraphy and paintings; his son, Gu Congyi (1523-1588), was a renowned collector of calligraphy and paintings in the mid-Ming Dynasty. Lu Shen and Gu Dingfang interacted frequently, not only because of their kinship but also because of their shared love of calligraphy and painting.

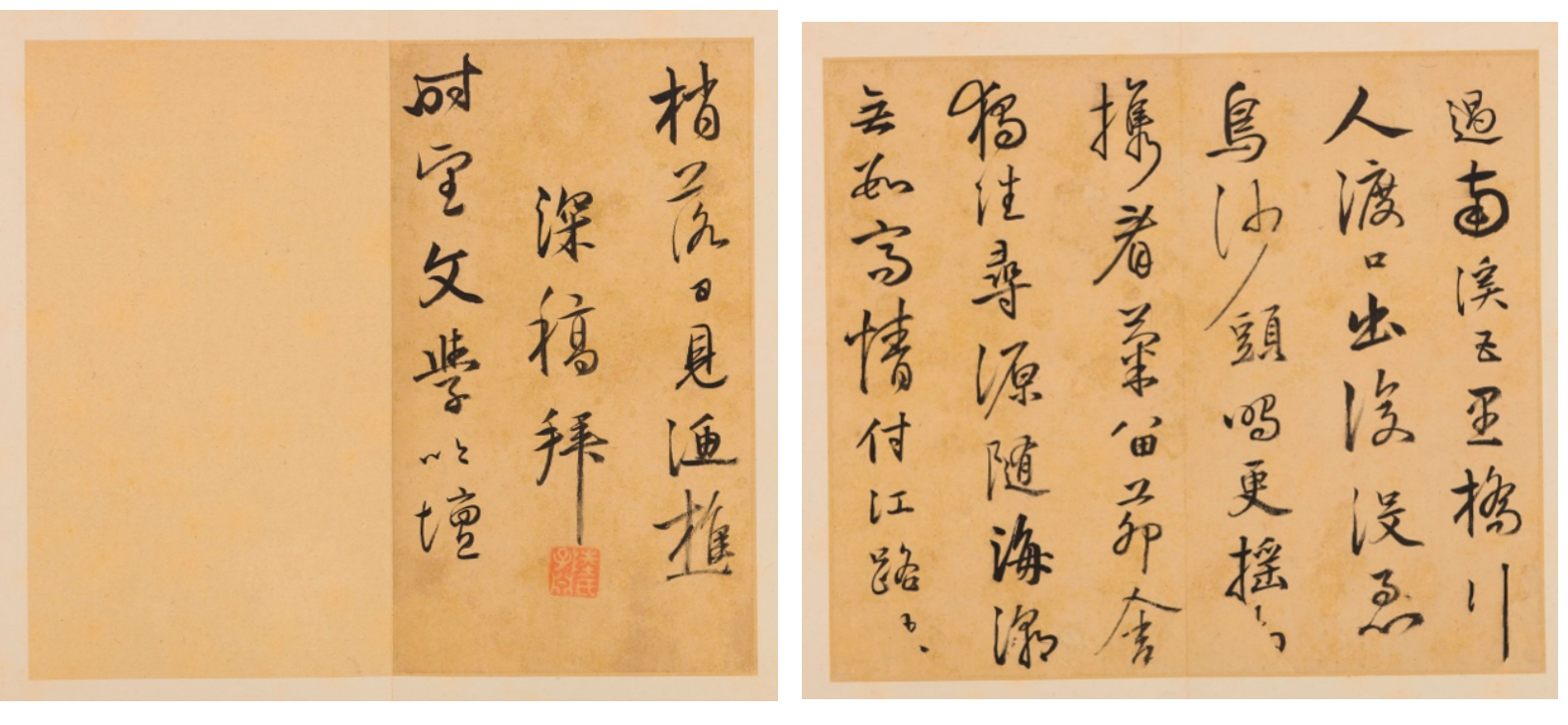

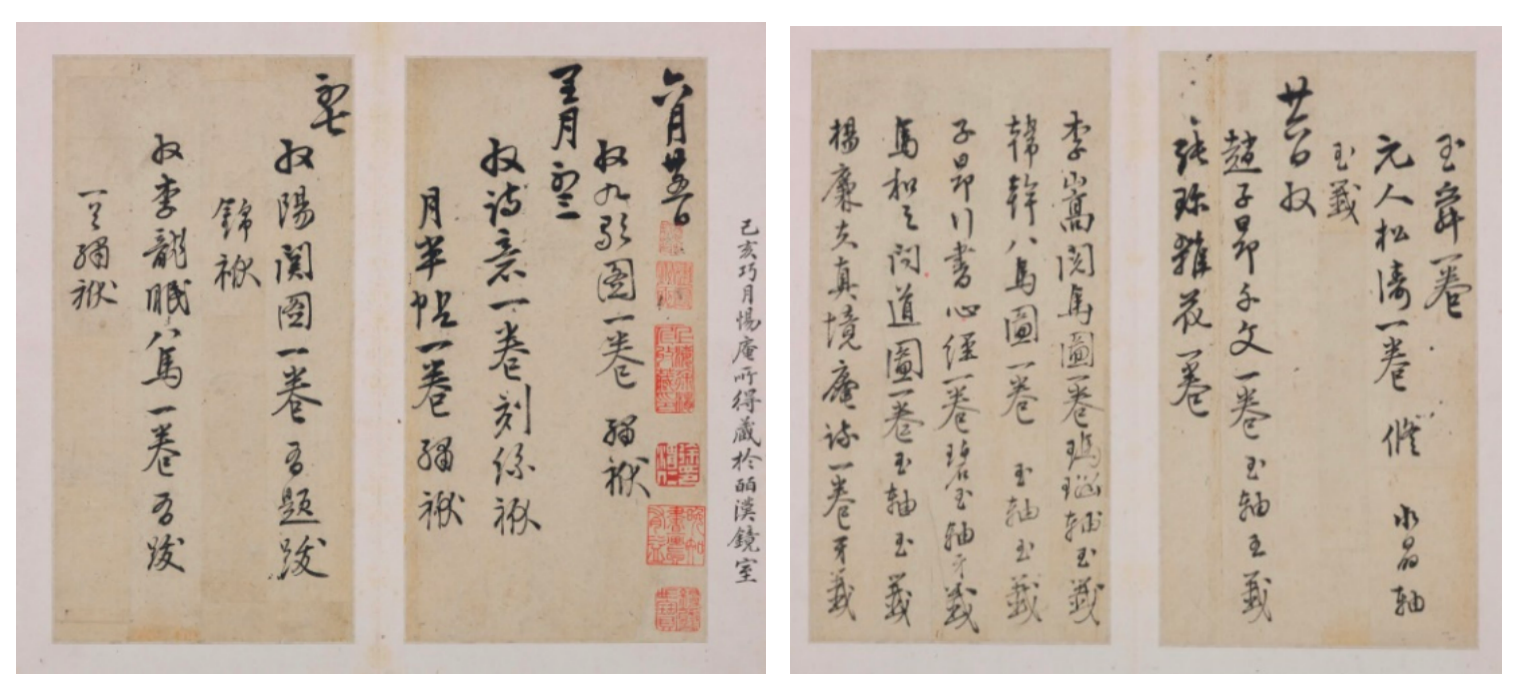

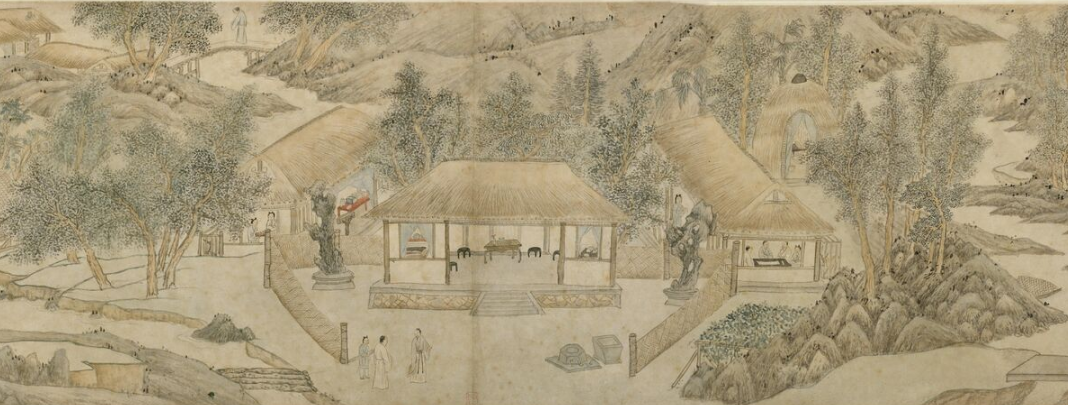

Lu Shen was an avid collector of calligraphy and paintings. In a letter home, he wrote, "Calligraphy and painting are the culmination of my life's work," and instructed his son, Lu Ji, to help him organize his family's collection of calligraphy and paintings. His "Draft of Calligraphy and Painting Collection in Running Script" (housed in the Shanghai Museum) records that he acquired 89 pieces of calligraphy and paintings within three months in a certain year (Figure 4). Yang Weizhen's "Fundraising Notice for Zhenjing Temple in Running Script" (housed in the Shanghai Museum) from the Yuan Dynasty is also included. In the mid-Ming Dynasty, the connoisseurship activities in Shanghai mainly revolved around prominent families represented by Gu (Gu Congyi), Lu (Lu Shen), Zhang (Zhang Yingwen), and He (He Liangjun). At that time, the scope of Shanghai's collecting had expanded to both sides of the Huangpu River compared to the end of the Yuan Dynasty. Today, Wen Boren's "Nanxi Thatched Cottage Picture" scroll (housed in the Shanghai Museum), painted for Gu Congyi, has been passed down, offering a glimpse into the thatched cottage and the scenery of the Zhaojiabang area of Shanghai five hundred years ago (Figure 5). The scroll of "Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies" attributed to Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (housed in the British Museum) and the scroll of "Running Script Shu Su Tie" by Mi Fu of the Northern Song Dynasty (housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei) were among the masterpieces treasured here at that time.

Figure 5 shows the manuscript of Lu Shen's calligraphy and painting collection from the Shanghai Museum.

Figure 6. A partial view of the "Nanxi Thatched Cottage" scroll by Wen Boren of the Ming Dynasty, housed in the Palace Museum, Beijing.

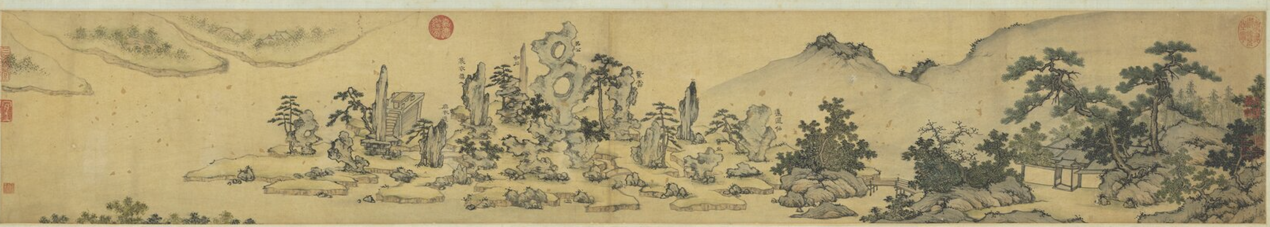

Besides Gu's Nanxi Thatched Cottage, gatherings of poets and painters were often held at Lu Shen's residence. When Lu Shen was serving as an official in the court, he would occasionally return to his hometown and reside in Lu's "Jiangdong Old Villa." In the second year of Jiajing (1523), the Houle Garden was built in the northern corner of the old residence. The "Yanshan Academy" was set up in the center, and the earliest collection of Chinese anecdotal novels, "Gujin Shuohai," was published here. One extant scroll, "Lu Shen's Yuanfeng Hall Meeting at the Immortal Mountain" (collected by the National Palace Museum, Taipei), was painted by Zhang Fu at Lu's request in the tenth year of Zhengde (1515) (Figure 6). From the painting, one can imagine the scene of Lu Shen and his friends reciting poems and unfolding the scroll in Lujiazui five hundred years ago. At that time, the Houle Garden had not yet been built, and the painting depicts Lu's old residence in Lujiazui, Pudong.

Figure 7. Zhang Fu and Lu Shen's "Gathering Immortals at Yuanfeng Hall" scroll, collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

The boat tour route described in Lu Shen's "Two Poems on a Two-Day Trip to Shanghai" album offers a glimpse into the dense network of waterways in Shanghai at that time. A network of canals, ponds, and streams crisscrossed the city, forming its transportation arteries. The area covered by this two-day tour route largely corresponds to the present-day central urban area of Shanghai. This is closely related to the changes in the water system of the Wusong River and the Huangpu River in the Shanghai area. In Lu Shen's time, the Huangpu River was gradually taking on its present form, thanks to the water management theories and measures of Xia Yuanji, Gui Youguang, and Hai Rui during the Ming Dynasty. In the early Ming Dynasty, Xia Yuanji oversaw the management of the Wusong River, achieving the confluence of the river and the Huangpu River, triggering a water system shift of "replacing the Wusong with the Huangpu." In the mid-to-late Ming Dynasty, Hai Rui further dredged the lower reaches of the Huangpu River, turning the Wusong River into a tributary of the Huangpu River, completing the "Huangpu River's capture of the frost," thus quelling floods and benefiting the six prefectures south of the Yangtze River. This established the Huangpu River's status as Shanghai's mother river, with far-reaching influence.

Today, elevated highways and subways have replaced waterways, and the former water town scenes are gone forever. Fortunately, calligraphy, paintings, poems, and prose have been passed down, allowing us to conduct "archaeological research" through these artifacts within the layers of urban renewal, achieving a connection between the contemporary and the traditional, and making the urban landscape both livable and enjoyable. The changing landscape and the enduring cultural memory serve as important evidence for the exploration of Shanghai's cultural origins and the "readable humanities" of Shanghai over the past millennium.

(Ling Lizhong: Research Fellow and Director of the Department of Painting and Calligraphy, Shanghai Museum; Wei Jiayang: Fellow of the Department of Painting and Calligraphy, Shanghai Museum)