Recently, Bi Gan's new film "Wild Era" has generated a lot of buzz and discussion. This film, which many consider "the most anticipated of the year," has been a source of curiosity ever since the official announcement of its cast, including Jackson Yee and Shu Qi. Since its premiere at Cannes earlier this year, its pioneering concept of immersing the audience in all senses—sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch—has further whetted people's appetites.

Bi Gan's "Wild Era" has a poignant premise—that humanity no longer dreams. When dreams disappear from this world, the hypnotist played by Yi Yangqianxi becomes a rebellious being, exiling himself into films, his body sleeping for a hundred years, while his soul repeatedly tastes the bitterness and sweetness of life in different forms of hedonism.

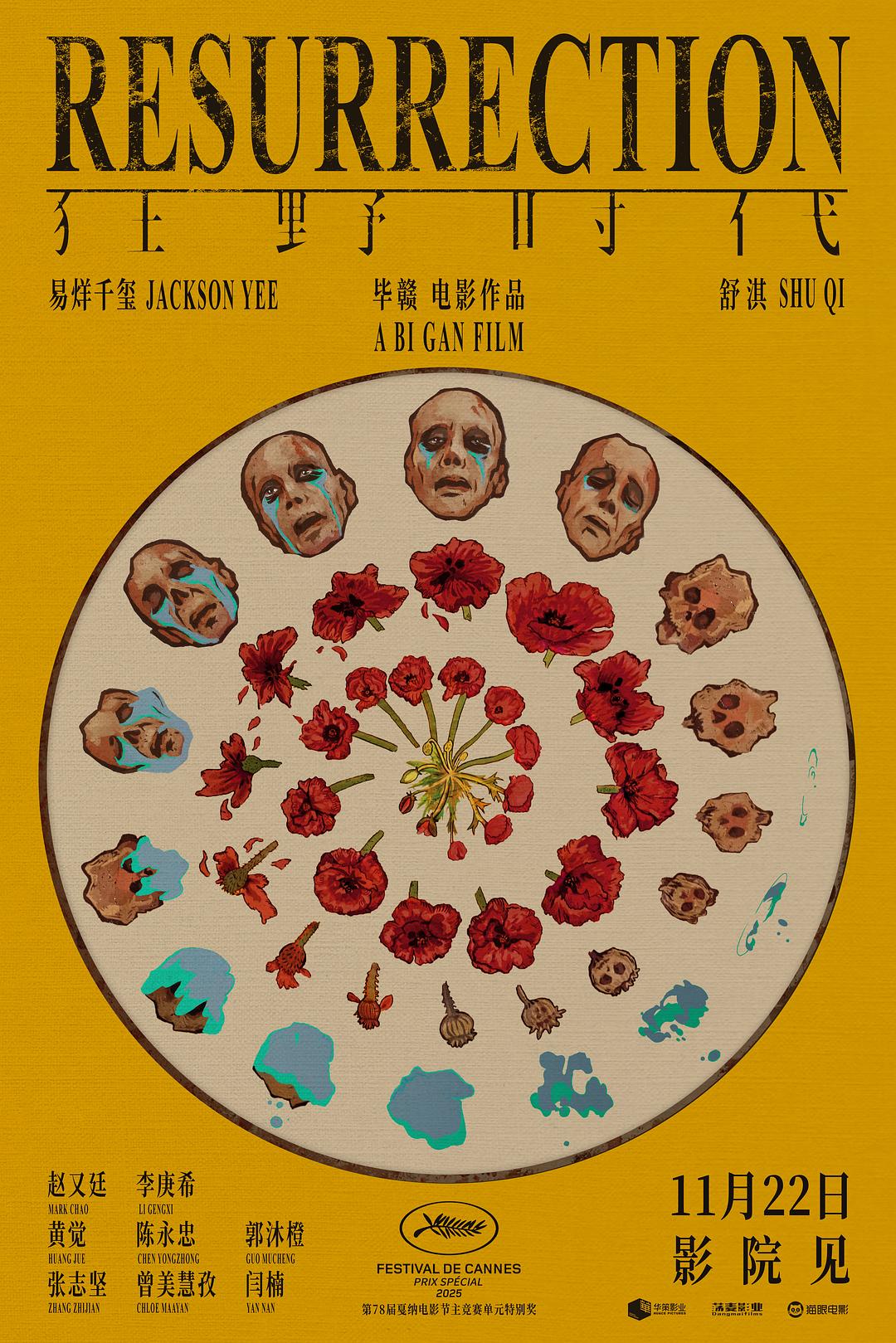

Wild Age Poster

Different dreamscapes feature meticulously arranged cinematic elements. This isn't a spontaneous improvisation, but a sophisticated experiment born from teamwork. In the first dream, numerous expressionist silent film elements transport the audience back to the initial conception of cinematic illusion a century ago. Western film, as a form of "circus entertainment," marked the beginning of humanity's ability to bring dreams into reality and share them. In subsequent dreamscapes, the audience encounters the dark suspense of the "Bourne Identity" and the poignant emotions of Gothic vampires. Each dream contains a story; the six senses—sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and thought—build the film's main structure. The content carried within each story, through a richer and more diverse sensory experience, further expands into a kind of "embodied" cinematic experience.

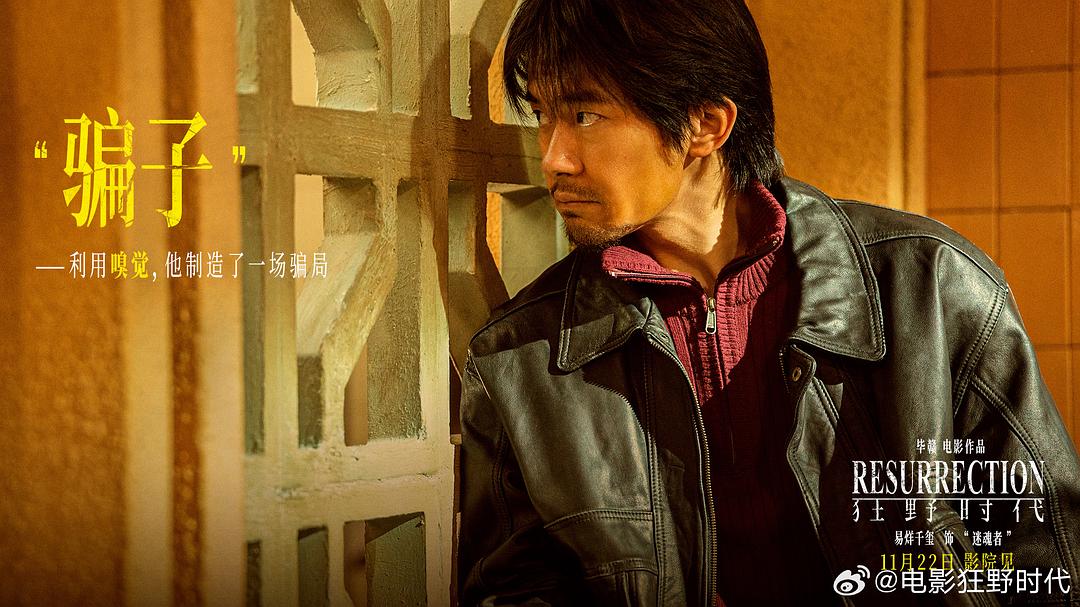

Stills from "Wild Era"

Having explored the vibrant poetry of *Kaili Blues* and the mesmerizing resurrection of *Long Day's Journey into Night*, Bi Gan presents a different picture this time. Filmgoers can still find elements of the ubiquitous "Bi Gan universe" in the film: karaoke, long takes, and of course, Chen Yongzhong, the "little uncle." He continues to employ every romantic means imaginable to traverse time, effortlessly creating a dreamlike atmosphere. However, this time, Bi Gan clearly possesses a grander narrative theme, with all his consistent style serving a narrative about an era that is gone forever.

For Bi Gan, becoming "more objective" is a "wild" thing.

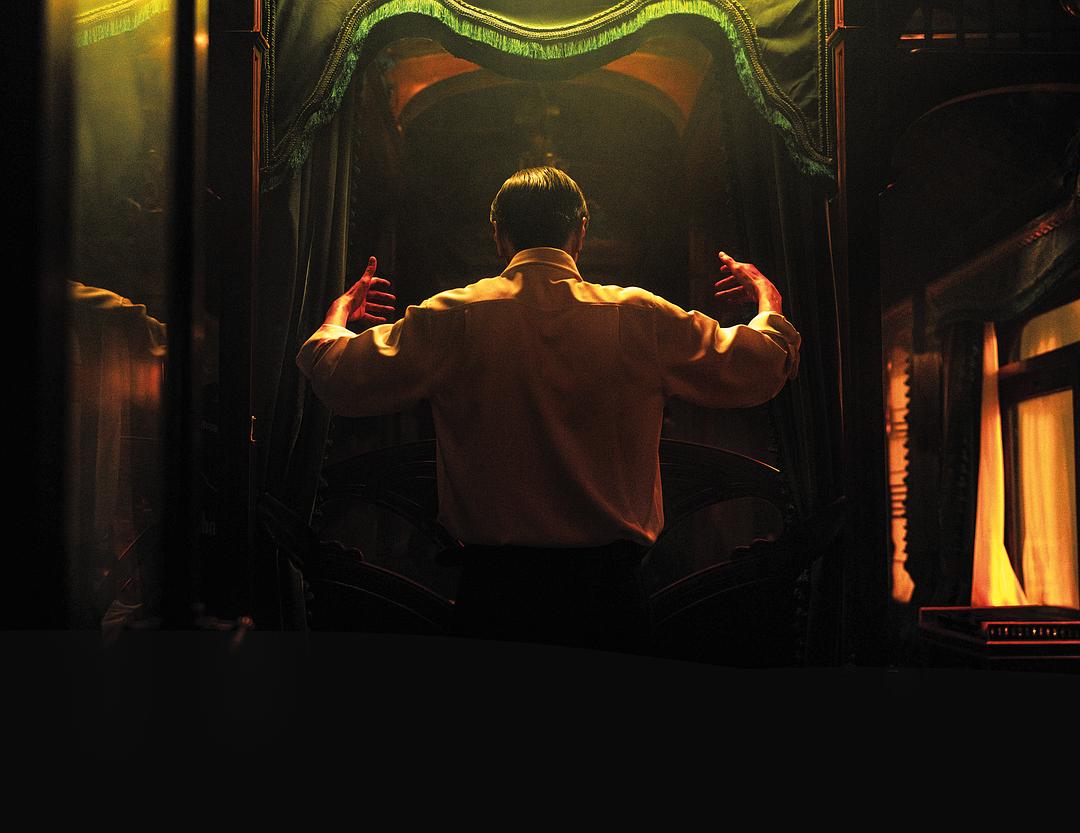

Bi Gan's signature KTV in "Wild Era"

Even though numerous interviews and film reviews have revealed many facets of the film, *Wild Age* remains a movie that audiences must experience in person at the theater to truly appreciate it. This "appreciation" stems from the creators' attempt to guide viewers beyond theatrical paths and audiovisual techniques. In their view, film should not be a passively received information product, but rather a sensory dialogue that requires active engagement and focus from the audience.

The interview with Bi Gan by The Paper took place on the first day of the film's release, during a promotional tour that took place at various theaters. Bi Gan, along with his co-stars, explained his sensory labyrinth to the audience through numerous details. In the past, he didn't like explaining his films, but now he says he sometimes feels "regretful," fearing that audiences might miss the film's most genuine emotions amidst the overwhelming amount of information.

We also tried to open up some perspectives through this interview to see how this video artist, who is committed to poetic expression, uses an old-fashioned language to build a fresh expression. In the face of this era where "humans no longer dream", what kind of visual response has he delivered?

Director Bi Gan; Photo by Xue Song, The Paper

Build a sensory passage

The Paper: Could you talk about the origin of the film, and what was the wildest part of its creation?

Bi Gan : The inspiration for the film is actually quite simple. I felt that the whole world was shrouded in a very powerful emotional force. Many people also talk about existential topics like "how people live in this world," so I put aside the script I was writing and thought about how to respond to this emotion. When I had doubts, I wanted to look back at that century and find the answers within it.

Because its creative starting point and final artistic result are quite different from what I've done before, the whole film is particularly "wild" in that respect. To be honest, my previous filmmaking was probably more personal, including the description of memories and literary feelings, with a high proportion of literature. Obviously, this film has much less literary feel and personal feelings; it's become more objective, and these are the "wild" parts for me.

A still from "Kaili Blues"

The Paper: It's been seven years since your last film. If we've seen you progress from low-budget to big-budget productions, and from amateur actors to working with big stars, from "Kaili Blues" to "Long Day's Journey into Night," in what ways do you feel you've grown and upgraded in your third feature film?

Bi Gan : From my personal perspective, it's definitely not an iterative or upgrading relationship; that's where AI upgrades. I constantly respond to the themes of the world, and as an artist, I turn these worldly issues into films and present them to the audience. Of course, my handling of the works becomes more and more mature, but in that process of maturation, many of the purest points about film and about emotions have remained unchanged.

The Paper: A very important concept in this film is to reach what you want to convey through the so-called "five senses and six senses". We always say that film is an "audiovisual art". When did you realize that other senses, such as touch, can also be a path to film?

Bi Gan : Although we use our senses to perceive and understand the world, it's amazing how these perceptions can form a kind of "synesthesia" in our memories. For example, when you think of your father, you might not first think of his face, but rather of your childhood and his scent. For instance, if I smell oranges, I'll think of my childhood. Synesthesia is frequently used in literature; it's a very common rhetorical device. In film, because dramatic construction is always considered more important, synesthesia is used less often. There's a natural creative connection between synesthesia and narrative, and this film attempts to continuously build that connection.

"Hearing" in movies

The Paper: When this feeling is projected onto the big screen, how do you feel about the quality of your "translation"?

Bi Gan : Because I had to watch the film repeatedly during post-production, my feeling was that each sense was well utilized within the story. But what I wanted to do was not to "translate" or simply transmit the senses to the audience, but rather to guide them to the narrative outcome through this sensory description, creating a path different from their previous viewing experiences. For example, in the past, we entered a film through its dramatic elements, but I think this film can be entered through other senses, and I look forward to seeing the results after everyone enters through these senses.

The Paper: What quality do you most hope the audience will grasp in the film?

Bi Gan : All these senses are encompassed within this century, and we have distinguished and organized them; that is our accomplishment. The audience needs to become true fascinated viewers, transcending these senses. I think the most important thing is the ending. After we break down the wall between film and reality, the audience, with that resurrected, complex life experience and the ability to dream, returns to their own lives. That, I think, is the most important thing.

What Bi Gan wants to say to the audience

The most fascinating part requires patience.

The Paper: This time there is a grander theme and a longer timeframe. Is this broader narrative span a challenge for you? In what ways does it connect with your personal feelings?

Bi Gan : I think it leans more towards personal descriptions and feelings about emotional relationships, but unlike his previous works which had some private details, it's about how a filmmaker deals with a certain period and how to summarize the relationships between people in that period.

The Paper: There are several father figures in the story, including their influence on the characters. Is this related to your own reflections on changes in your identity?

Bi Gan : It's probably a more general distillation. On a personal level, everyone has a memory of their father; it's a common denominator, a consensus in my heart. So it involves many interpersonal relationships, including my own experience as a father. Therefore, when facing children, I can place that empathetic feeling within a specific era, combining it with a grand emotional narrative to ultimately convey it to the audience.

Some viewers have asked me why the snoring sound is so long. For me, it's a very good summary, a summary of the kind of sound that a father and child can never forget. When people experience those sound designs in the theater, they will feel that they are beyond our experience, and that it is just a point in daily life that has been infinitely magnified.

The Paper: Your films have often been described as "difficult to understand." Recently, you've done many interviews and participated in various promotional events, where you've tried to explain things such as characters or motivations. What is your attitude towards explaining your own films?

Bi Gan : Because this film contains many simple and genuine emotions. I'm not actually trying to explain, but I sometimes feel a little regretful, worried that people might overlook those emotions. The overall richness of its audiovisual presentation is very high; viewers will enjoy the aesthetics of its audiovisual language. But the most captivating part of this film, in my personal opinion, is precisely the very simple and genuine emotions between people across different chapters and periods of that century: the feelings and emotions we have with our closest relatives, friends, and first loves.

Wild Age Poster

The Paper: How would you define the film "Wild Age"? What is it to you?

Bi Gan : I think Wild Age is definitely an art film, its genre is beyond doubt. Many genre films are very clear, but art films actually encompass many film genres; it is itself a cross-genre combination.

Yi Yangqianxi is playing all the audience members.

The Paper: Many people say that "Wild Era" is a love letter you wrote to the film. You love the film so much, so why is Yi Yangqianxi's first appearance so "ugly"?

Bi Gan : Because the goal was to have the Bewitching One transcend a century, to traverse time, I didn't want his true appearance to be portrayed. Also, the Bewitching One character, as everyone who watches the film knows, is referring to the audience here; his hunchback is due to a distorted cinematic gene within him. From his initial appearance and costume, he transforms from a monster to different characters in other stories, and finally reverts to being a monster, forming a closed loop in his image. The century the film spans can be effectively summarized using historical language.

Yi Yangqianxi's monster look

The Paper: Jackson Yee is the soul of this film; he's younger than all the actors you chose before. At what point were you certain he was capable of taking on this important role?

Bi Gan : I had this intuition from the beginning. But that intuition wasn't about judging whether it would be him or not. Rather, it was about how we would collectively handle the outcome of this "wild" production, and what support systems we would need. The choice of actors was based on considerations for creating the final artistic result. Creators and audiences understand things from two different perspectives. From our perspective as creators, whether it's actors or directors, it's about how to achieve it. For example, how to portray a monster convincingly. Actors need to translate material into concrete actions; in short, it takes a lot of effort. This film, in particular, required a lot of effort.

Dying again and again in my dreams

The Paper: This role doesn't seem to be based on real life like traditional movies, so what are your working methods?

Bi Gan : I think professional actors have many ways to communicate when they work together. Actually, these roles are all very challenging. The special effects makeup for the monsters is very time-consuming, and at the same time, the performance requires getting close to the monster's inner world. But the specific performance is not abstract. For example, how many degrees his waist should bend, how his hands should be supported, these are all very practical areas for communication between the director and the actors.

People might be interested in the inspirational moments, but this wasn't just a spur-of-the-moment decision; it wasn't something we filmed based on a dream. Rather, there was a very systematic and rational underlying logic in its creation. For example, there were many literary consensuses surrounding this monster, and these consensuses have given rise to many other characters in film history. Take *Edward Scissorhands*, for instance; it might be a bit dark, a bit gothic, but it also needed to fit our desired aesthetic. I wanted the character to be like an unborn child, chaotic, so the entire design of his face went in that direction. Ultimately, this resulted in an understanding based on a shared consensus that the monster is kind at heart but ugly on the outside, leading to this final product.

Special makeup makes Jackson Yee look forty years old

The Paper: In the fourth story about the sense of smell, Jackson Yee plays a character who is actually more weathered than his age. This role represents a breakthrough for him.

Bi Gan : Yes, we used some special makeup techniques, which took a lot of time to make him look older, ideally around 40 years old. We did a lot of testing. The entire pre-production process involved a lot of effort. For example, we spent two or three months creating a model, then applying the makeup to the actor, and simultaneously filming a test scene to confirm if it matched our vision. Only then could the actor begin to develop and perform. The final moment in the film felt so real because it involved so much hard work from everyone, including the actors' portrayal of their characters. During the months we prepared for the various special effects, Qianxi had to observe many middle-aged men. He's an actor with exceptionally good fundamentals, and it was a very happy thing for everyone to work towards a common goal.

The Paper: Inviting a top-tier actor like Jackson Yee to star in a film inevitably means bringing the movie to a wider audience, which will naturally bring more controversy. Because people are increasingly aware that film has entered an era of audience segmentation, would you prefer your audience to be those with specific professional backgrounds, or would you prefer to interact with more strangers?

Bi Gan : Actually, I never thought about making any demands on the audience. Now, in my third film, no matter how it changes, the respect for the complexity of human nature has never wavered. Starting with *Kaili Blues*, at the most crucial moment, when the uncle's song was sung, it was a moment that words couldn't express, yet we were all deeply moved. This film also holds the same respect for human complexity, which has always been important to me. I feel that the audience has invested their time to come and watch a film, and I try my best not to disappoint them on a cinematic level.

At film festivals, because there are more films on display, people are more knowledgeable about cinema, and there are many film enthusiasts, the discussions tend to focus more on film aesthetics and techniques. These are technical aspects that we should be working on, so when our films reach a wider audience, what's more important are the moving moments within them. Like the character Ku Yao, played by "Little Uncle," who's like a father to us, sitting across from us, during the heaviest and most painful ten or twenty minutes, he's constantly joking around. In those moments, I hope the audience can understand them.

Watching movies serves as a coordinate of public memory.

The Paper: Compared to the previous film, Long Day's Journey into Night, the production of Wild Age has improved. How do you view the influence of the film industry on you?

Bi Gan : The three films dealt with different aspects of the film industry. This film isn't a single movie, it's five parts, so for the production team, after each segment was filmed, they had to stop and rebuild a new worldview because it consists of five systems. The film industry is actually pursuing cost reduction and efficiency improvement, but besides being a product, film is also an artistic achievement because it ultimately aims to resonate with people's hearts. I hope to use all the time and costs saved by the film industry to benefit the film itself. This is what I've been doing for the past few years.

Stills

The Paper: This year marks the 30th anniversary of World Cinema and the 20th anniversary of Chinese Cinema , leading to much discussion about the history and future of film. With cinema being impacted by numerous other forms of entertainment, is your recounting of the century-long history of film tinged with a certain "sadness"?

Bi Gan : I think movie-watching habits have definitely changed a lot now. Our attention is more scattered, which is a characteristic of this era, and a characteristic that is a common choice of humankind. So if you ask me if I find movies sad, I rarely consider that question. The reason is that I rarely treat it as a truly important issue in my mind.

The film contains many scenes that pay homage to film history.

What matters to me is not the medium of film, or what it will ultimately become, but the way stories are told—whether it's told through the silver screen or not. What I care about most is that many people sit in one place watching a story; this is a foundation of our shared memories.

I think what we've truly lost over the years is our shared memories. The relationships that make up the world—comprising countless individuals and countless others—are being fragmented. The shared experience of going to the same space, witnessing the same story at the same moment, is precisely what makes film, in its secular sense, so important to me. Only after experiencing something together, many years later, do we have a coordinate when we recall a particular moment. Now, the coordinates of our lives are constantly being dissolved and lost, and this, I feel, is the beginning of surrendering our souls. I don't want to surrender my soul, and this issue itself isn't about film.